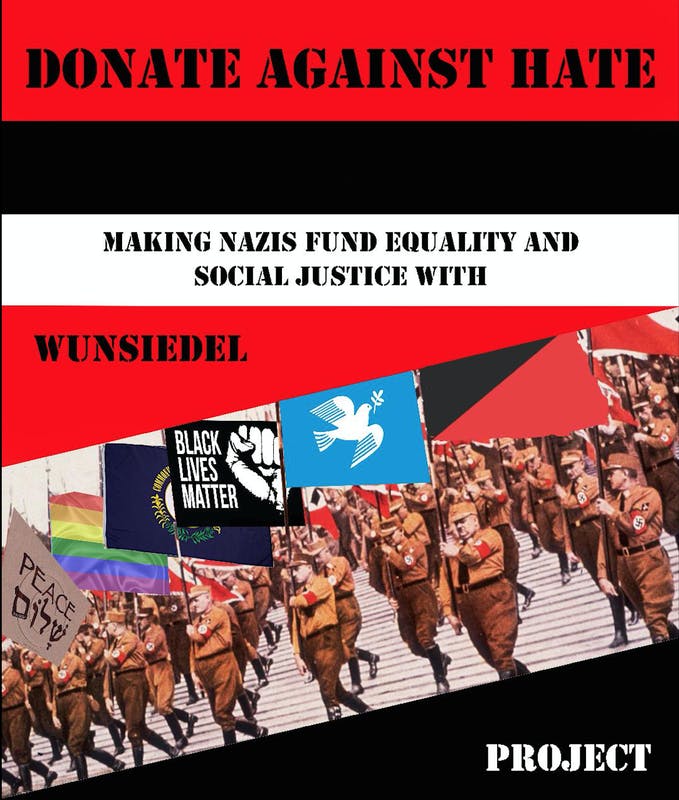

Wunsiedel Project

By Anonymous

Credit: Fred Table

My family tells me that for several days after November 8th, I curled up on the couch and cried inconsolably. I barely remember that week, as I was frozen with terror for my family and other loved ones. When I told my children what had happened, my 11-year-old, an immigrant and Latinx child, asked if she should leave the country and go “home”.Like millions of parents with children of color, the months leading up to the 2016 election were a nightmare unfolding before my eyes. Already aware that my kids are potential targets of race-based violence, it was horrifying to see blatant bigotry become increasingly more acceptable everywhere we turned. I had to watch the news late at night, so that the kids would not hear their future president shouting racial slurs to cheering crowds. The silence within the GOP was equally disturbing.

As an Archeology major, I studied Nazi Germany, and extensively studied the genocide of Indigenous Tribes in North, South and Central America. I knew what was coming, and the fear for the safety of my family grew with each new racist statement and policy plan coming from the campaign of 45. I practically screamed from the rooftops to anyone who would listen that we were heading toward genocide.

Once my devastation from election day shifted into action, I reached out to other families and activists in my community, seeking the most effective ways to resist the white supremacist politicians and groups growing in power and visibility.

Neo-Nazis in Wunsiedel, Germany stand before a table full of bananas laid out for them as part of a brilliant protest against their march. (Credit: Rechts Gegen Rechts video)

I happened upon a news story about Wunsiedel, Germany. Outraged that Nazis had an annual march in their town to honor Nazi officer Rudolf Hess, the community transformed the march into a fundraiser for anti-hate efforts. It was a massive success. I immediately reached out to the local activism groups I moderate, and asked if anyone wanted to do this in our city: Lexington, Kentucky. Nazis had threatened to rally in Lexington in response to the upcoming relocation of Confederate statues.

The night that I started the Wunsiedel Project page, only 35 people signed up, and I panicked and nearly deleted it. I told my mom, “I can’t do this — I’m not an organizer, and I’ve never run a fundraiser!” She counseled me to wait until morning to decide.

Within one week, over 1000 people had signed up for the planning group, and around 150 were following our public page. We quickly decided on the charities we would support, SPLC (Southern Poverty Law Center), and Kentucky Refugee Ministries. I reached out to these groups, and coordinated a process for donations, so that we could track the success of our project. An artist volunteered his time to create our poster and Facebook page design. Several members printed and distributed posters around Lexington and Louisville. A news reporter in the group connected us to a friend, and our project made the local newspaper.

Here is the thing about Wunsiedel Project: we have not needed one penny for our organizing to make this happen! Every part of this effort is a grassroots, community response to hate. We are not willing to allow Nazis to rally in our city without a strong message of resistance to bigotry, and a strong showing of solidarity for equality and justice for all people.

We committed early-on to anonymity as a group, to prevent egos and infighting from damaging our good work. We also wanted to provide safety for all of our volunteers, many of whom are directly targeted and threatened by Nazis and other hate groups. Another priority was ensuring that families feel safe participating, as many of our founding members are parents who wanted to find a way for children to participate in this resistance effort. Kids were able to help put up posters, and my own kids delighted every time I told them how many people were in the group, or how much we raised for justice.

Confederate statue removed in downtown Lexington, October 17, 2017. (Credit: Screenshot from video taken by Caitlyn Stroh, Lexington Herald Leader)

This week, our city relocated the Confederate statues without notice, thus removing the Nazi’s purpose for their rally. Coincidentally, we paused our fundraiser the night before (not wanting to focus on the Nazi rally that had apparently been postponed!) Instead, we had decided to focus on amplifying urgent efforts & calls to action from organizations lead by, and in service to, people targeted by oppression.

Our project remains open, and we now hope to spread the word about how other cities can use this model. Our mission is to ensure that whenever hate groups attempt to rally in U.S. cities, they will unintentionally raise money for charities that are the antithesis of their goals — groups that help refugees, combat hate crimes, promote equality under the law for all people, etc.

For more information, folks can check out our Facebook page, Wunsiedel Project, where they can message us directly to learn how to do this in their own city.

One news story about our inspiration in Wunsiedel can be found here.

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe