Raising Multiracial Children, Part 2: Anti-Blackness in Multiracial Families

In Part 2 of this conversation about raising multiracial kids, our guests - Drs. Victoria Malaney Brown, Marcella Runell Hall and Kelly Faye Jackson - return to discuss anti-Blackness and how anti-Black messaging shows up in multiracial families (including non-Black families). Referencing recent examples from social media, our guests breakdown three common myths that perpetuate anti-Blackness within multiracial families, and describe how these myths negatively impact the identity development of multiracial Black children specifically. We also talk about concrete steps that parents and caregivers can take now to actively reject White supremacy and anti-Blackness and build resilience as a multiracial family.

Find the lightly edited transcript below and related resources below that.

Be sure to check out the previous conversation in this pair, Raising Multiracial Children, Part 1: Examining Multiracial Identity.

EmbraceRace: Hey, folks. Hey, everyone. Welcome. This is the second part of a two-parter, the first time we've done a two-parter on raising multiracial children. And the first one was called Examining The Complexity of Multiracial Identity. It was fantastic and it was a great first part to lead into this conversation, so you might want to check that one out after if you haven't.

And tonight, the conversation is a bit different. The title of this conversation is Raising Multiracial Children: Dismantling Anti-Blackness in Multiracial Families. We know that anti-Blackness is prevalent in the US culture, around the world really. It's globally prevalent. And that that messaging really does show up in multiracial families even when they're non-Black families. None of their races are Black, but still anti-Blackness shows up the way White Supremacy does, right? Those are very related.

So we're going to talk about how it shows up in multiracial families, in particular, with our fabulous guests. And they will talk about the certain myths that allow anti-Blackness to be perpetuated in multiracial families, and talk about how those myths negatively impact multiracial children in their identity development and what we can do about it. We'll come to concrete steps.

Welcome folks, and welcome to you. Welcome to our guests. We are live on Facebook and on Zoom. Let me introduce you. I think the most of you, for sure, most of you who are sort of attending or watching this, attended the first part, so I'm going to cut down a little bit on the introduction.

We have three fabulous guests back with us after being here on Thursday, Dr. Victoria Malaney Brown is a multiracial scholar, practitioner, and soon-to-be mom of a multiracial son. She works at Columbia University and actively researches how multiracial college students experience racism and engage with the racial justice.

We also have Dr. Marcella Runell Hall, who is the VP for Student Life at Mt. Holyoke College, and an affiliate member of the Center of Racial Justice and Youth Engaged Research (CRJ) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She's also a White mom committed to anti-racist, pro-liberation parenting, raising two young daughters who identify as Black and mixed. Welcome to you both.

Welcome Dr. Kelly Faye Jackson, who is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Work at Arizona State University. Kelly is a social worker and a multiracial person who examines the identity development and overall wellbeing of people of mixed racial and ethnic heritage. She identifies as a mixed Black and White person, and resides in Phoenix with her partner, her young daughter and their puppy.

So good to have you back. Last time, again, Part 1 was really about introducing folks to the complexity of multiracial identity. And we ended that, and there was a lot of complexity there, and we ended that with a question about how are you feeling, right? A lot of change, a lot of flux, a lot going on for multiracial people, multiracial identity, the politics of that. There's a shared concern about anti-Blackness, and a sort of powerful strain of anti-Blackness in multiracial socialization in some homes and so on.

What brought each of you to this topic of anti-Blackness in multiracial families? And Victoria, we'll start with you.

Victoria Malaney Brown: Sure. Thanks again for having us tonight. I'm excited to kind of talk a little bit more on a deeper level with those joining us this evening. But what kind of brought us here together was in 2017 actually, so we've been thinking about this topic for some time. We all attended the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in American Higher Education. I was asked to help moderate a conversation on a topic that was called Can White Family Members Truly Ever Get It? Biracial Individuals Navigating Racial Justice Conversations within Interracial Families.

And so that's what started it. Marcella and Kelly were two panelists, we also had additional panelists as well. But the broader conversation was a yearning for folks that were in that conversation to talk about Whiteness, to talk about what it means to be mixed and multiracial, and to be somebody in that conversation when you're talking about anti-Blackness too, and how that then is always inherent in the conversation. We can't separate those pieces out.

And so more recently once the new wave of Black Lives Matter occurred with the death of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and countless others, Kelly reached out and said, "Hey, let's kind of have this conversation. I've been noticing these things happening online in the mixed and multiracial community spaces. Let's talk more about that."

So that's what really brought us together as a group, and then we wanted to kind of think about ways in which we could discuss this a bit more broadly. I think it's also important though, just to mention our positionality upfront, for those of you who did attend the first webinar, you learned a little bit about my background, but I want to say that again in case this is the first time you're joining us.

So I identify as multiracial. I identify as an Indo-Caribbean American. Indo-Caribbean really stems from the Caribbean in particular Trinidad, but other islands as well. I'm also Spanish, White and Irish and do have African roots. But I come to this work as part of my personal life experiences growing up in the South, particularly in South Florida, and now living in the Northeast for some time.

And my stance on anti-Blackness is it's the root of oppression and racism in the United States, right? And so in knowing this, inherently, the monoracial Black experience is very different than being someone who's multiracial. And yes, can have Black roots or have Blackness in their heritage, but the way you're treated as a monoracial identified Black person, or if someone perceives you as such, is very contrasting to someone who's mixed and has light skin privilege and other things. So I just wanted to mention that. And it needs to be acknowledged.

Mixed people need to acknowledge their privileges and be in support of Black communities and families.

EmbraceRace: Amen. Thank you. And Kelly.

Kelly Faye Jackson: Yeah. I just really appreciate you allowing us the space to have conversation with folks about this, because this was exactly what I was seeking when I reached out to our previous panel members is let's have a conversation. So some of the things that I was observing, I think, that was really troubling to me, was that in multiracial spaces, folks were minimizing or ignoring the importance of Black Lives Matter. Also kind of centering multiracial experiences and kind of saying that they're somehow more important than the experiences that are happening right now in our Black community.

The other thing that I noticed was I saw that the multiracial community was deliberately separating ourselves from BLM. So you might have seen like statements that would come out, Latinx for BLM, and then I saw some Multiracial People for Black lives. And I think for me personally, as a mixed Black, White woman, I felt offense to that, I think because it assumed that we were separate from these communities or that you can't be both/and. So I think for me that was something that I struggled with and really wanted to talk about.

I think also why it's an issue within the multiracial community has a lot to do with our history in terms of the Multiracial Movement and the original organizing by predominantly White parents to have a multiracial category on the census.

So for us, in kind of studying the Multiracial Movement, we recognized that those efforts that there was some anti-Blackness surrounding those efforts for mixed Black and White children. Their parents were really trying to give them a different label that wasn't about acknowledging their Blackness. So for me seeing some of that, it just kind of reinforced this history that we already have. And so, yeah, that's how we kind of came together, and just appreciate the opportunity to have this difficult talk. I think all of us are kind of still having conversations about this and are new to this and are continuing to challenge each other, so thank you.

Marcella Runell Hall: Thank you. I just want to say I'm incredibly honored to be a part of this conversation and this panel. And I shared a little bit very briefly last week that I grew up in a family of two White parents. My background is Irish American. I moved around a lot and had a lot of different experiences because of that in relationship to interracial friendships and interracial dating relationships even in my childhood.

And so before I ever had language for being an ally, accomplice, co-conspirator, that was the work I was trying to engage in. And obviously that is even more important right now in this moment in time, and in particular because of my proximity to my family and raising two daughters who, as you heard, identify as both mixed and Black in our family with my husband, who also identifies as Black.

And so this is important for me personally, but also professionally because this idea of anti-Blackness is directly connected to something that I think is uncomfortable sometimes to talk about in these spaces, which is this broader notion of White Supremacy.

White Supremacy is this belief that Whiteness is superior to other races, to other backgrounds. And fundamentally that the systems that we have in the United States, the policies, the practices, the history, the cultural norms, all of that has been shaped by that fundamental core belief that is sort of baked in to our experience. And so that's an important place to start, and we're going to talk a lot more about that, but I wanted to just name that as my perspective coming into this.

EmbraceRace: What is the definition of anti-Blackness? And can we clarify if the term "biracial" or "multiracial" is preferable?

Kelly Faye Jackson: Sure, I can take that on. And just quickly, I think it really depends on the person in terms of how they want to identify. I have a lot of close friends who identify as biracial, and I think that's completely fine. I think some of us have chosen not to kind of partialize what we are because sometimes it reinforces biological beliefs in race, but really it's about where the individual is at in terms of how they want to identify.

EmbraceRace: So the idea that you're 50-50 is kind of not a thing, given our history [Black enslaved women being raped by White men regularly] and the construction of race, is a fiction.

Kelly Faye Jackson: Yeah. Right. For anyone who's ever taken a genetic test looking at ethnicity, we know that those percentages are very often wrong. Some of these we talked about last time we spoke, but wanting to just go through them really quickly. So the first is kind of how we think about race. So I tend to like Omi and Winant's definition of race as a learned social identity that is ascribed by others in society.

So when you start thinking more critically about race, we recognize it's not a neutral system, and that it's often invented and then reinvented by mainly White people in power to kind of protect Whiteness and White Supremacy. So for multiracial people, we saw this in using the rule of hypodescent or the one-drop rule in categorizing multiracial people back in the day. So as early as the 1890 census, we saw terms like quadroon, like a quarter Black, octoroon on the census. So just wanting to be aware of that, that this is kind of entrenched deeply in our history.

Racism, so thinking again from a critical race framework, racism involves one group having the power to carry out systemic discrimination through the institutional policies and practices of the society, and by shaping the cultural beliefs and values that support those racist policies and practices.

What I like about the work that's being emphasized now by Dr. Kendi is that he puts it kind of quite simply. So to be racist is to be engaging in these policies and practices or believing in them and kind of perpetuating these ideas.

And finally, a term that's really close to the multiracial community, a relatively new term, is monoracism. So this is the systemic social oppression that targets individuals and families who do not identify with monoracial categories. And this just wanting to plug Dr. Jessica Harris, Dr. Marc Johnston-Guerrero, and Kevin Adell and Eric Hamako, who really kind of gave us the terminology to kind of describe some of these experiences.

And really quickly, some of these experiences include racial identity patrolling. This is when people eyeball you to try to figure out what your racial background is. Racial litmus testing, so this is when people kind of give you that idea of, "Well, you're not Black enough. You're not Asian enough," based kind of on your cultural behaviors or appearance. And the final one that is our classic history that is multiracial people, it's really difficult to shake, is the racial passing. So this is the assumption that multiracial people, who claim multiracial identities, or those who look White are passing as White or secretly wish to be White. So we kind of put together a slide to talk more exclusively about delving in right now to anti-Blackness. So we're going to kind of pull that up and kind of think through. I'm a very visual person, and I think my panelists also feel that way, and so sometimes it's helpful also for us to kind of visualize what these things mean. [See Kelly's slides here.]

[Monoracism] can look like... racial identity patrolling. This is when people eye value to try to figure out what your racial background is. Racial litmus testing, so this is when people kind of give you that idea of, "Well, you're not Black enough. You're not Asian enough," based kind of on your cultural behaviors or appearance. And the final one ... it's really difficult to shake, is the racial passing. So this is the assumption that multiracial people, who claim multiracial identities, or those who look White are passing as White or secretly wish to be White

Dr. Kelly Faye Jackson

What is anti-Blackness?

Kelly Faye Jackson: First, anti-Blackness is the historical and current violence exercised against Black people at all levels of personal, interpersonal, cultural, political and economic life. And what I like about this definition, and this is by Ana Cecilia Perez, is that the author defines "violence" very broadly. So this can mean from undermining and not respecting Black persons or Black leadership to mass incarceration and the murder of Black people by police.

So we included a couple images here to see how broad anti-Blackness can be. So the first, we see a representation of cultural appropriation. So this is the co-opting of a historically oppressed group's culture with little to no acknowledgement. This first image is an example of how some folks, in this case, an Asian male is sporting locks, which we know is a hairstyle that traditionally associated with persons of African heritage.

The second image depicts colorism, which is the prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone. Now, this one is really, I think, difficult because it's really rooted in White Supremacy and sadly has been internalized by a lot of us and many other historically oppressed racial groups. So those are some of the things that will help us get to understand a little bit about the complexities of anti-Blackness and how it might show up.

Three Ways Multiracial Families Perpetuate Anti-Blackness

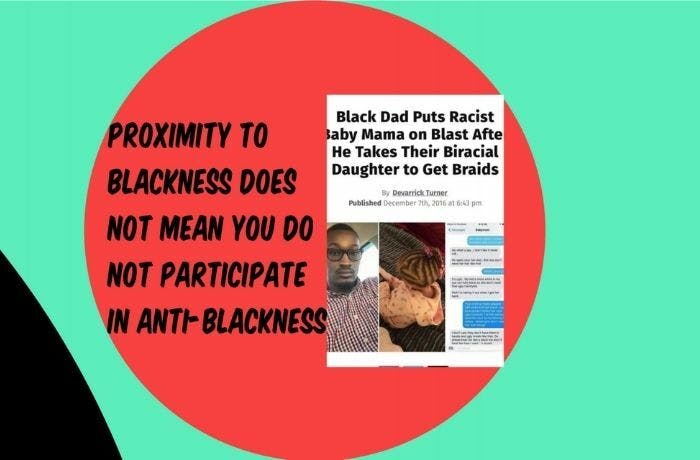

1) Proximity to Blackness does not mean you do not participate in anti-Blackness

Marcella Runell Hall: Yes. So we're going to talk about proximity to Blackness for a moment, because one of the things that gets said often is this belief that someone can't be racist because of their partner, friends, family, et cetera. So I want to first go back to what I just said about the roots of all of this, right, that this is embedded in our systems, this is embedded in our practices and policies.

So it is never just about interpersonal individual conscious behavior, it is far more complex than that. So that's the first thing. The second thing is, Angela Davis talks about this idea, right? In a racist society, it's not enough to be non-racist, we need to be anti-racist, and Ibram Kendi's work is really taking that to a whole another level. I think that proximity to Blackness question is situated in that non-racist category that isn't really actively interrogating the ways that White Supremacy or that Whiteness shows up in our families.

Here's an example from social media. A Black dad shared a conversation that he had with his former partner who identified as White about taking their daughter who identifies as, in this article, as biracial or mixed to get her hair braided, and all of the conversations that happen between them that show up as the mom really saying, "She's not really Black. I don't want her hair to look like that. That's not an attractive hairstyle." All of those anti-Black sentiments, right?

So this is both her daughter and her former partner, and this is the way that she's showing up because she's internalized this about hair that is different than hers, about different hairstyles, et cetera. And so the reason that we're sort of calling this out in particular is that, that idea that there's an automatic protective covering that you have because of your relationships, is actually really damaging and can be harmful.

What it is though, of course, is an opportunity for you to think and do better, right? To do it differently. And so I would invite everybody to think about this proximity question in relationship to your own unlearning. So the degree to which you're learning about the history of race and racism in the United States, the degree to which you're incorporating new paradigms, vocabulary to combat anti-Blackness, and the degree to which you're doing your own self-work.

Those things, coupled with relationships, can actually then be transformative and anti-racist, but without the work and the knowledge, the relationships in and of themselves are actually, in some ways, unfortunately, can actually be amplifying anti-Blackness with that or recreating it and certainly not dismantling it.

The degree to which you're learning about the history of race and racism in the United States, the degree to which you're incorporating new paradigms, vocabulary to combat anti-Blackness, and the degree to which you're doing your own self-work. Those things, coupled with relationships, can actually then be transformative and anti-racist, but without the work and the knowledge, the relationships in and of themselves are actually, in some ways, unfortunately, can actually be amplifying anti-Blackness with that or recreating it and certainly not dismantling it.

Dr. Marcella Runell Hall

2) Fetishization of Multiracial People- A form of Anti-Blackness

Victoria Malaney Brown: So in the next example, we're going to talk about the fetishization of multiracial people. So fetishizing multiracial children is a form of anti-Blackness, in the sense that you may have heard in, possibly in your own family, experience the comments that family members can make about your child. Particularly their skin color, their hair type, maybe their eye color, and then comparing that to maybe other family members who may have different features, but making it seem that it's negative to have Black features, Black hair.

And when that happens it sends this message around Blackness not being beautiful, and we don't want to do harm and create ways in which there's a hierarchy of thinking of what is beauty and what is supposed to be. All of it is always connected to Whiteness and lightness, which is also something to always think about if you're thinking about this on the spectrum. "How am I perpetuating this?"

And unknowingly, we often do this unconsciously, which is also why bias is connected to this conversation too. We unknowingly say these slight comments that then can actually do more harm than we realize to our children. They then start to internalize that racism and then it can create other issues further down the road. Some examples that you see in the picture around this one woman who was at a recent Black Lives Matter protest that says, "Stop shooting. I want mixed race kids."

That example, Kelly actually had seen online, and the connotation, the meaning behind that is just really unfortunate that this woman is out there saying that. The other piece to think about is what privileges some of the multiracial community is the fact that we often get comments around being very unique, beautiful, having these particular features, right? Even comments about, "Oh, I can't wait to see your mixed baby," or, "I can't wait to see what they look like." Well, in some regard, when somebody says that to you, you're like, "Oh, well." You could think that's just something they're trying to be nice in saying, but also if you think more critically about it, "What are they actually really saying?" They're also possibly also connecting that to some feelings around anti-Blackness too. So that's something to also consider.

And then thinking about how this conversation continues over a lifespan, we talked last webinar about developmentally, when you have children that grow into emerging adults and enter into that college phase, where I do a lot of my work, this still follows to be the same. And there's also been studies that have been looked at where multiracial women in particular are at higher percentages to experience sexual assault over other racial categories, which is also something interesting to consider and think about in the topic. Yeah. But Kelly can say more on that. She knows more about that particular study than I do.

EmbraceRace, Melissa: So yeah, this is all great. I was just thinking about, and you guys will talk after, I suppose, about how this affects kids and of course what we can do about it, but just thinking about making someone proud in their own skin in this context of anti-Blackness and White Supremacy is super tricky. Right? I just think about it with our own daughters.

We're all kind of different shades, and I'm the lightest, and Andrew is the darkest, and we're sort of all in between. And just, I remember doing a lot of the blacker the berry stuff [i.e., using the expression “the blacker the berry the sweeter the juice” to affirm darker skin], and one of my daughters said to me finally, "Mom, do you hate your skin?" and I just sort of had to go like, "Oh, I have to think about that." And to reframe it, because you really are so aware of what you're countering that you can kind of lay it on heavy, and that doesn't always work either because the lighter kid can feel like not a black enough berry. So anyway, a challenge, I'm feeling that for sure.

Kelly Faye Jackson: Yes, we all are feeling that I think as parents, and also a lot of us who are multiracial as adults are continuing to kind of grapple with these things. Especially when it comes to kind of exoticizing multiracial people, a lot of us did, growing up, clung to that as a sense of pride. People paid attention to us cause we were mixed. So really trying to think differently about what that was about and how often who we exoticize is usually mixed with White, that it's not just about being mixed race in general, but that White Supremacy kind of looms over even how we exoticize multiracial people.

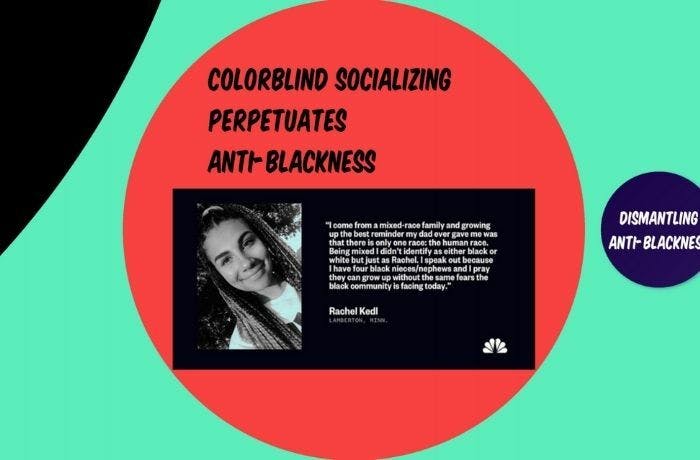

3) Colorblind Socializing Perpetuates Anti-Blackness

Kelly Faye Jackson: So I want to talk to you a little bit about color-blind parenting and socializing with our children. And I want to come from a very honest place in saying that when parents engage, and this is not just parents, but caregivers and helping professionals, when we deploy or use color-blind socialization, we're coming from a loving place, I believe. Often, parents are thinking that they're protecting their children, prolonging their exposure sometimes by minimizing race, prolonging their exposure to discrimination or racism. Or even for White children from them becoming kind of racist themselves or adopting some of these beliefs and thoughts.

When you think about parents, some of us have never experienced discrimination personally, maybe we don't recognize how our child's experience is different from our own. So we see that with multiracial families and transracial adopted families when parents haven't lived the experience of their children, so it's hard for them to understand it or empathize with it.

And honestly, some of us have internalized shame around our racial group memberships, and I think a lot of us are only beginning to really love and appreciate ourselves and our Blackness, so recognizing all of these things to be true. So we're coming from a place of love, but then really having to accept, swallow the pill that color blindness really isn't helping our children when it comes to any of our children. Whether they're White, Black, mixed, Asian, it's not really helping.

So here's why. It minimizes and further separates particularly multiracial Black children from their Blackness. And we talked last week about the strength that comes with having a Black identity or having an identity with a historically oppressed racial group. So when you minimize that or when you say, "Everybody is just human," you kind of prevent that child from being able to connect to something that they can feel pride about, so I think that's one way.

And the example that I have in this screen, I saw this posted on Facebook. It reads,

"I come from a mixed race family, and growing up, the best reminder my dad ever gave me was that there is only one race, the human race. Being mixed, I didn't identify as either Black or White, but just as Rachel. I speak out because I have four Black nieces and nephews and I pray they can grow up without the same fears the Black community is facing today."

So for me, it really shows, it really visually represents kind of this conflict within this child, this young adult about who she is. So she talks about being raised as human, and then she later goes on to quote, and separate herself from her Black cousins and Black family members and then the Black community. And you see the contradictions in the hairstyle that she's adopted, the fact that she sees herself as separate, but also recognizes in how she kind of chooses to express herself, that there is a connection. So again, by not talking about these things and talking about race, our children are kind of on their own to have to figure it out.

And what we've seen from the research is that they're really ill-prepared. So when we use color-blind kind of parenting, they're really ill-prepared when they do, and they will, come across racism, discrimination and prejudice. So from our research, and this is with emerging adults who are in their twenties, they're still recalling instances where they've brought up this issue with their parents about race, and their parents either minimized it or dismissed it completely or ignored it.

So even when our children ask and are seeking information, some of us, because of our own uncomfort, because of our own shame, because we want to protect them and spare them from talking about race, are disadvantaged and are left to trying to figure out the stuff about race on their own. So where are they going to get those messages? If they're not getting them from you, they're getting them from social media, they're getting them from movies. And often when you look at kind of representations of race in these sources, they're very much based on these kind of biological existence of race, which we know is not true, but which I think is continuously perpetuated.

So again, it's more about us thinking how we can protect our children. Yes, I wish this country was not as focused on race as it is, but I also recognize how there's a lot of strength that comes with having pride in being a member, particularly of the Black community, knowing that African Americans have historically built this country. So there's a pride that comes with that, but that we have to, as parents, caregivers, teachers, educators, helping professionals, really nurture that with our children.

Yes, I wish this country was not as focused on race as it is, but I also recognize how there's a lot of strength that comes with having pride in being a member, particularly of the Black community, knowing that African Americans have historically built this country. So there's a pride that comes with that, but that we have to, as parents, caregivers, teachers, educators, helping professionals, really nurture that with our children.

Dr. Kelly Faye Jackson

EmbraceRace: Thank you. I was wondering about non-Black multiracial families and how anti-Blackness shows up there. Is it different from how it just shows up generally in all families, right, especially if you're not White, because there's kind of very clear messages about sort of trying to assimilate, if you can, and trying to get the good stuff- the money, the power, the status of Whiteness.

What does anti-Blackness look like in multiracial families that are not Black?

Kelly Faye Jackson: So I can just speak to how colorism also influences those different groups who are not mixed with Black, but who also have kind of sometimes internalize the idea of the racial hierarchy, so this idea that some racial groups are better or worse than others. So things that I've seen in my research has been multiracial young adults talking with their parents, and their parents making comments like, "Yeah, I don't care who you date or who you bring home, as long as it's not a Black person."

So those are some of the things that at least we see in our research about anti-Blackness, so there's almost this removal from, or "you just can't do this with Black people", that is pretty prevalent. But I imagine Victoria and Marcella see other examples too.

EmbraceRace: Can you clarify the difference between "passing as White" and "White presenting"?

Kelly Faye Jackson: Yes, I can take that or other folks can take it. It's not the same thing. So presenting as White is that other people see you as White, but that's not how you identify yourself. So often people see me, as I've gotten older, as looking more White, but that's not a way that I identify. Passing as White, and I think often we think this as happening a lot. We see in the media constant stories retelling of passing, but it's when the multiracial person claims to be White. And navigates through the world as a White person.

EmbraceRace, Melissa: So like Nella Larsen. When my dad came to this country, he lived in Black Harlem with his aunt and uncle, and they couldn't go to White Harlem to visit people from his island who were passing. So it sort of has that connotation, right, as opposed to presenting.

EmbraceRace, Andrew: If we say that identity is certainly subjective to some degree in that people can choose their identities, there's a connotation in passing which implies that you're pretending somehow to be something that you're not. This seems at odds with the idea that people should be able to choose certainly how they identify themselves. Just any thoughts on that? Do we say that today, that people pass as White or pass as anything else for that matter?

EmbraceRace, Melissa: I mean, they do.

Victoria Malaney Brown: -again, it's still just all connected back to where we started in this country. I mean, you think about how passing originated from where this is really connected to supporting the Black folks who are enslaved in the South.

Like, having other Black folks who maybe had light skin because of the violence of, if we want to talk plantation masters and what they did to the Black women that were on their plantations, like it again harkens back to the extreme violence that our enslaved Black communities experienced and their ancestors several generations ago. But still that violence still perpetuates even in today's 2020 society, but we see it in different ways.

So yeah, it's so complex. It's important to know when we talk about dismantling anti-Blackness, we're going to talk more about the education component and this critical self-reflection that's needed to kind of move us forward.

Tangible Steps to Dismantling Anti-Blackness

1) Critical Self-Reflection- Educate Yourself!

Victoria Malaney Brown: Yeah. I think generally the biggest piece is thinking about this in your own way of self-reflecting. I mean, we talked a little bit about that at the first webinar. That it's important all of us as individuals we come to our life, hearing all kinds of messages from our youth all the way up to our adulthood.

And there've been so many memories and conversations over that time that you have filtered and taken in maybe unknowingly or knowingly of how you perpetuate this anti-Blackness piece in your life, whether it's skin color, whether it's connotations of you don't want to go to that particular community because of X reason, or you think something negative towards a Black student. I mean, there are rates of Black boys and girls who are given more suspensions and other types of behavioral infractions even from a young age all the way up to high school, which then maps out to mass incarceration and all of the other pieces that all connect.

But I think what's important, how can you dismantle that? Take stock in like what you have learned. What is challenging about that? What education do you need? If you don't know the history of the United States, a good book to read is Howard Zinn's People's History of the United States. I mean, that's a great read that can kind of show you how a lot of these things are all connected to history.

But it's a lifelong process, like how are you complicit and acknowledging anti-Blackness? Is it that in your community, are you living in a homogenous White space? Are your schools that you're sending your children to predominantly White, or we would call like historically White in higher education? How can you challenge that by offering different opportunities to engage with different folks in your community? And then recognize the impact of internalized racism. So how does that then impact your parenting practices?

The importance of therapy is great too. Every single one of us needs to do our own self-work to be able to know our histories, not only what you can figure out about your own family and ancestry, but knowing the histories of the people that you surround yourself with too. So it's a part of practicing dialogue and asking good questions and not being afraid to kind of dive into understanding new things about your family or the people that surround you. So those are some examples around continuing to educate yourself. What do you know? What do you not know? And then how can you then translate that to your children at different ages over their lifespan?

How are you complicit and acknowledging anti-Blackness? Is it that in your community, are you living in a homogenous White space? Are your schools that you're sending your children to predominantly White, or we would call like historically White in higher education? How can you challenge that by offering different opportunities to engage with different folks in your community? And then recognize the impact of internalized racism. So how does that then impact your parenting practices?

Dr. Victoria Malaney Brown

EmbraceRace: Critical self-reflection. Other strategies?

2) Be a Counter-Agent! Interrupt anti-Black and racist narratives. Create Counterspaces.

Kelly Faye Jackson: Yeah. I was just going to mention, and you see down there a box that says being a counter agent. So often a lot of the messages that our children get, that we get ourselves, perpetuate these ideas of White Supremacy, again, colorism, anti-Blackness. So being an active kind of parent is to kind of interrupt these messages before your children kind of internalize them or take them on.

3) Expand Your Networks!

So one way to build the counter spaces is to build community, and that will be something Marcella talks about and expanding your networks. Finding spaces where your child is around other both monoracial and multiracial people that represent their various racial heritages is very important. I was thinking, in the past, when my parents found their own group, which was for multiracial families, and I can honestly say until I became an adult and sought those spaces myself, that that was one of the only times that I ever was around other children that were mixed that looked like me.

It was so affirming to kind of be in that space as a young person, so much that in my 44 years it still stands out as something that's really important. So needing to kind of build space for your children, especially for those of us who are living in homogeneous environments. And what we mean by that is, if you're living in settings that are mostly one racial group, or if your network of people is mostly one racial group, when your child is mixed with other things, other racial groups, you need to be able to incorporate those people in your child's life.

So that's why I think it's so important to have those counter spaces where people can feel affirmed and talk about their experiences around being both multiracial and also a member of these different historical class racial groups.

Marcella Runell Hall: And I'll just add a few things to this. I think that one of the things that happens for White parents in multiracial families is that things might not always be obvious to you in terms of what is feeling like a microaggression or just a plain old aggression to your child.

And so one of the examples I just want to share with you very quickly is that my youngest child was in preschool, and there was a princess day, and I call this like the princess hair moment, where she came home and was talking a lot about Rapunzel, and a lot about Rapunzel's hair, and how most of the other kids in her class who all identify as White or had the type of hair texture that could easily look like Rapunzel when they were playing, were really getting into it and they wanted to do princess hair and Rapunzel every day for that week.

And it was a child-centered play group, and so this play was being generated by the kids, but it was obviously not at all neutral or inclusive. And my daughter's hair is like type 3A curl. That did not reflect her, and so it was harmful. And she expressed it in her frustration, but it was my job as the parent then to advocate, and to interrupt, and to provide alternatives and to have the conversation with the teacher.

And I would just say if that wasn't your experience growing up, that might not be obvious to you. You might think that that is a small thing, and I would say that there are many things like that, that happen all the time with our children. And I would also add that race is hyper-visible oftentimes for multiracial kids.

I used the example last time about they're constantly looking to organize the world and to figure out where they are sit in and who's going to match with who in families and all of that. And yet it is often not discussed at home, right? So both hyper-visible and top of mind and then not discussed, because there isn't a shared vocabulary or there isn't the opportunity to continue to learn and grow and talk about race at home specifically.

And so I would say that, a couple of things that I just want to add, validate your children's experiences. If they describe something to you that sounds like a microaggression, validate that. This isn't the time to play the sort of perfectly logical explanation role as a parent, right? This is the time to say, "Can you say more about that? How did that feel? What can we do about that? Would you like me to talk to this person? Would you like to talk to this person? What are some strategies that we can do moving forward?"

4) Representation Matters!

Marcella Runell Hall: And then I would also say that having discussions about all kinds of media that you're consuming and children's books is really important, because if left not to discuss, that will automatically reinforce the standard of beauty around Whiteness, because that's what the media does, right? It reinforces that, so if you're not actively seeking out representation. Children's books alone, just as an example, in 2018, 50% of all children's books featured White characters as the main character and 27% featured animals, which means 77% of all children's books that came out in 2018 were about White characters or animals, leaving a very small slice that was actually about kids of color.

And so I would say you might think you're doing a lot at home, but it is likely in school in another places that it is the dominant narrative that is being reinforced, and that your child isn't likely to see themselves in very much that's happening if you're not actively seeking that out.

So the final thing that I'll say about this is the extending your networks piece. Often, this is the conversation that comes up about where to start. If you are not in touch with your child's family of origin or your partner who identifies as a person of color, how do you find your networks? I would say, this is where play dates are really important. This is where play groups are really important, right? If you're not invited to one, start one, right? Start a playgroup for other kids of color. Start a space where your kids can get together and have reflection of who they are and their identities, or find committees or places you can serve and be useful in your unique perspective, right?

If you're doing yourself work, you're doing your learning and unlearning and you're in your relationships, you actually could be really useful in these conversations, and that might be another place to find extended network. So those are just three tangible things that I wanted to make sure to underline, because I think this is a lifelong commitment as you know, but our neutrality in this is not an acceptable position.

When it comes to our families, there is so much that is being shaped by those intimate relationships. And I just want to underscore that in our families, that is often where our kids are getting hurt the most, right, because it is other family members comments about hair or skin, or who you look like, or what percentage of whatever you identify with. And that actually isn't about what's happening out there, that's about what's happening right in our spheres of influence in our immediate families. So that's where you need to get bold and you need to feel like it's okay to make decisions about who can and can't have intimate access and relationship to your child, and you need to get comfortable with confronting that. The research really does show that if you don't do that, the harm that gets done, the internalization of that kind of racism coming from family members is very hard to unpack later, and it creates all kinds of fractures in families and in communities. I'll just end with that.

EmbraceRace: Yeah, thank you, Marcella. I hear that. Absolutely. In the case of multiracial children, there's often a lot of attention especially to the, if you have a White parent and a parent who identifies otherwise, the question becomes often, "How do we support a healthy multiracial identity that accommodates the “of color” part?" right? But Marcella, actually, last time you talked about your mixed and Black daughters, and your older daughter in particular on St. Patrick's day. And how to have her saying to her teacher maybe, "No, really, I have an Irish mom. This is my day, not just because we're all Irish on St. Patrick's Day."

Here’s a question in another direction: How do I find or how do I support my multiracial child in having a healthy White identity, right? How do I support my child to not in effect reject or prioritize his, her Black, Brown, et cetera, identity over the White, which feels like it's also part of who they are? Any wisdom on that?

Marcella Runell Hall: I hope everyone else will chime in on this. I mean, I think that for me, talking about oppression without also talking about liberation is really harmful. So I think it's very important that we are using vocabulary in our homes, not just about race and racism, but also about liberation and what does that look like. Because the oppression dehumanizes all of us. It dehumanizes the people who identify as White, it dehumanizes people who identify as people of color. And so that shared vision around what would liberation look like? You get to be your whole self. You get to show up and talk about all of your identities in an integrated healthy way and other people receive that. Right?

I think that for me, talking about oppression without also talking about liberation is really harmful... And so that shared vision around what would liberation look like? You get to be your whole self. You get to show up and talk about all of your identities in an integrated healthy way and other people receive that.

Dr. Marcella Runell Hall

Marcella Runell Hall: So for me, I think it is really important to give examples of everything in history, from abolitionist to civil rights activists, to how people are forming coalitions now and supporting racial justice movements from all different backgrounds. I actually think that's really important. There is a ton of imagery about White people. There is NOT a lot about White anti-racist activism in popular culture that is able to be translated to children. Right? So I think that those role models are important. Those stories are important, and so for me, I think the humanizing and the liberation piece becomes critical.

EmbraceRace: All right. That's great, Marcella, thank you. Victoria, you wanted to weigh in on that?

Victoria Malaney Brown: I also just think about the questions, right, that were just asked. I mean, you think about what we started with this conversation about White Supremacy and Whiteness. Like, the way I understand the concept of why it's being asked around how do I not have my child lose that sense of Whiteness, but that's actually kind of the message that we're trying to counter today. Your child won't lose that sense of their Whiteness. They're growing with your families, and it's dominant in the US society that Whiteness is best, and that lightness can give you access to all these privileges.

What we're trying to say is to counter a little bit of that, which is why this conversation is so challenging. I have a White father. By identifying with my Indo-Caribbean heritage, do I negate his existence? I think of it, as Kelly mentioned at the beginning, it's both/and. So I identify as Indo-Caribbean, White, Irish, and I don't separate those things out when I discuss my race. That's a healthy way of discussing that, and it doesn't negate my Whiteness either. It doesn't say that I'm denying my Malaney heritage or my White family members, but at the same time it also embraces my Caribbean family members too. It doesn't distance them nor negate those ancestors and those relatives I've learned about my culture from.

So I think it's hard to be able to think about well I need my child, or I need my family member to also understand. I think it's about both/and. So you have to notice too that as your child grows, they are going to identify with different things over their lifespan. We talked about fluidity last time about multiracial people. There's going to be different points in time where your child and your young adult eventually will identify, look, culturally connect to different pieces of your family's history. They may negate it, they may accept it, but that's part of the mixed experience. So that's just something I want to stress.

So if you're a White parent, don't despair that your child is negating you in any way. I think it's just a matter of the process and being comfortable to allow them to explore.

EmbraceRace: Absolutely. So we're near the end of our time together, but I was wondering, in terms of empowering having these conversations at home and creating that environment as we can, when we can, while our kids are little and as they get bigger. They're out of the house more and more, but I'm wondering about that teacher piece or that classroom piece, and just thinking about how now a lot of classes ask people how they identify gender wise on the first days. I can imagine doing the same in a school, once you're talking about how one identifies themself and how they tend to be identified. Or maybe just starting with the, "How do I identify myself?"

We're almost starting school possibly virtually. What strategies can teachers utilize in those first weeks to set the table for multiracial and other kids?

Marcella Runell Hall: I can send a link when you send things out after. Two activities that I use when I teach all the time are the name story and life mapping. Life mapping is longer, but the name story can be done very quickly, and gives students a chance to talk about the history, origin, meaning of their names. Their first name, middle name, last name, nicknames, how they got their name, what it means, if there's a cultural connection.

Often that sets the table for students to disclose whatever they need or want to disclose about their background on their own terms in a moment when it's very appropriate to be sharing about your name and how you want people to call you in a particular space. And so I would say sometimes it needs to be in a way that is really on the terms of the student themselves, right? I think that the idea, particularly for younger kids, to have to go around and name categories that they might not yet have figured out is very hard, and so I think that putting it in your own words, giving space for that and role modeling that. "My name is Marcella and it means this, and this is why it's important to me," is a good way to do it.

[For the name story exercise, see p. 11 of this PDF curriculum. Also read Kelly's important caveat below.]

Kelly Faye Jackson: I just want to mention too, in considering that activity, some children might not know, particularly children who are transracially adopted, might not know about that history, so that might also be something that the teacher can encourage kind of conversation, or have the child kind of embed their own meaning for their name.

These are other things that you can do. I think you have to communicate with your teacher, I think you have to advocate for your children, make sure that representation of multiraciality is in the school, whether through the curriculum, whether through different books in the library. And also make sure that the forms are not being monocentric and restricting how our children are identifying, is a good first step.

EmbraceRace: Victoria, any thoughts on this question?

Victoria Malaney Brown: I mean, I would just echo what Kelly just mentioned at the last part about the forms. When you're filling out as a parent your child's race, that question comes up. And I even think about this when this happened to me as a young kid, and even still in my thirties I can recall this. In Florida, I don't know whether they still do this or not, but they would literally call your name and like say your race too to confirm, like in the roll call, which was so interesting now that I think about it. And there wasn't at the time an ability for parents to check multiple boxes, so my mother always just said, "Check other," because that was the only option we had. So that would be something that I just always struggled with as a kid, like thinking about, "What does that mean. How am I 'other'?"

But that's a whole another conversation on the multiraciality and like the experiences, but I think it's important to know that if you notice things like that in your school surveys or in your school forms as a parent, like be that person to have a conversation with the principal or whoever is the appropriate person to say, "This is limiting. This doesn't give my ability to check multiple boxes for how my child identifies."

So those are other ways that you can actually help to change and shift what Kelly is mentioning, the monocentric functioning of policy and practice that happens still in education. So that's just one thing to just kind of keep note of and mindful of. And then we see it in a lot of other systems too, but if there's an ability to change it, and as a parent you have a lot of power in the school systems in certain respects, like that's one way you can kind of navigate.

EmbraceRace: That's great. Thank you so much. Thank you all. I mean, I would also say, as for teachers, don't assume by looking at someone and maybe teaching kids, when you read a book, that we don't know how someone identifies. "Where do you think this child is from?" We don't necessarily have to know. We might think we know, but we shouldn't assume.

Thank you all and goodnight. Bye.

Resources (return to top)

History of racism and anti-Blackness:

Dismantling Anti-Blackness in non-Black communities of color:

- Ending Silos - Counteracting anti-Blackness and doing better generations to come

- 30+ Ways Asians Perpetuate Anti-Black Racism Everyday

- It's time for non-Black Latinx people to talk about anti-Blackness in our own communities — and the conversation starts at home

- South Asian anti-black racism: 'We don't marry black people'

- Being or Nothingness: Indigeneity, Antiblackness, and Settler Colonial Critique by Iyko Day

Impact of racism and anti-Blackness on multiracial children and families:

- Anti-Blackness and adoption, JaeRan Kim, Harlow's Monkey blog

- Samuels, G. M. (2009). “Being raised by White people”: Navigating racial difference among adopted multiracial adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 80-94.

- When they say the fight against racism starts at home, they aren’t lying, Jeneé Osterheldt, Boston Globe

- My Wife Is Black. My Son Is Biracial. But White Supremacy Lives Inside Me, Calvin Hennick, WBUR

- Franco, M. and O'Brien, K.M. (2020), Taking Racism to Heart: Race‐Related Stressors and Cardiovascular Reactivity for Multiracial People. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 48: 83-94.

- The damaging effects of fetishizing mixed race children, Alexandra Ferry, Twentyhood

- What it’s like to be biracial and arguing with your white family right now, Brittany Wong, HuffPost

On Colorism:

- Take a colorism implicit bias test at Harvard's Project Implicit

- Emotional Effects of Colorism, Good Morning America, YouTube

- Can we talk about colorism?, GEM Naturals, YouTube

- Dark Girls and Dark Girls 2 Documentaries, OWN TV, YouTube

- Colorism in the Latinx community, MTV Decoded, YouTube

- Light skin privilege, MTV Decoded, YouTube

- Shades of Black - series on colorism in the Black community

- Same family, different colors: Confronting colorism in America's diverse families, Lori L. Tharps, Beacon Press (2016).

Dismantling racism and anti-Blackness and supporting multiracial children:

- "Mom, you don’t get it”: A Critical of Multiracial Emerging Adults' Perceptions of Parent Support, Atkin, A. L.*, & Jackson, K. F. (in press), Emerging Adulthood

- 10 Ways to Support Multiracial Students, ACPA Multiracial Network, Buzzfeed

- How to talk to your mixed race kids about race, Sonia Smith-Kang, Mash-up Americans.

- Raising multiracial kids in a racially divided country, Marj Kleinman, Scary Mommy

Resources for helping professionals:

- Combating Anti-Blackness and White Supremacy in organizations recommendations for anti-racist actions in Mental Health Care By Dr. Babe Kawaii-Bogue. For a copy email: AntiRacistActionGuide@gmail.com

- Competencies for Counseling the Multiracial Population (Kenney & Kenney, 2015)

Victoria Malaney Brown

Marcella Runell Hall

Kelly Faye Jackson

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe