Racial Socialization as Resistance to Racism, the Early Years

When families work to help their children understand race and racism, they are engaging in a process known as racial socialization. To understand how racial socialization can be used as a tool for anti-racism, there is much to learn from families who have been racially marginalized and the lessons they have taught their children.

Watch this conversation in which we explore racial socialization as a vital form of parent and caregiver involvement and discuss strategies that resist and disrupt racism when socializing young children, ages 0 to 8. We’ll be speaking with Dalhia Lloyd, program specialist in family and community at the Buffett Early Child Institute. We’re also joined by two parents of young children, Keeley Bibins and Ben Heath, about their approaches to helping little ones understand race and racism and be actively anti-racist.

EmbraceRace: Tonight we're excited to be talking about racial socialization as resistance to racism. We've touched on this in other conversations, but specifically we're going to talk about the early years, zero to eight, and what racial socialization is and how to use it to raise anti-racist kids of all stripes.

We have three guests today, but we will start out with one and we'll invite the other two on later.

EmbraceRace: Our first guest is Dahlia Lloyd. Really glad to have Dahlia who has been dedicated to ensuring that early childhood systems and practices support young, diverse learner's, optimal development and learning. She's been doing that work for 20 years. Dahlia is a family and community program specialist for the Buffet Early Childhood Institute, where she provides coaching and support to school-based family facilitators. Her research interests include racial socialization, implicit bias in early childhood, and sociocultural classroom interactions. Dahlia, welcome.

Dalhia Lloyd: Thank you for having me. I'm excited to be here.

EmbraceRace: Wonderful to have you. And Dahlia, we're going to start with you in the place we usually start.

For folks who do this work, there's almost always a personal investment. What is it about you that brought you to the work that you do?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. So as long as I can remember, I have been really interested in the social construct of race and how that feeds into racism. And I would say that my personal life, my professional life and the intersection of both of those have played a major role in what has brought me to this work. So in my personal life, I'm raising two children. I have a boy and a girl, and I've helped them both through navigating some racialized experiences. Sometimes their experiences are the same and sometimes they're different. For my daughter, I can recall having conversations about hair texture, skin tone, and body types. And for my son, I remember having conversations with him about staying close to me when we are in grocery stores, because I was afraid of how someone may view a little Black boy running around a grocery store, right.

So in my professional life, I've been an infant teacher, a toddler teacher, and a preschool teacher. I've also been a director. In my role as a director, I've had parents come to me and say, "Hey, my child has reported these negative racialized experiences. What do I do? What do I say? How do I approach this?" And so I leaned on my own experiences as a mother to be some type of a guide in that conversation, because I didn't have the right answer either. I, as a parent, was trying to figure that out myself. And so I tried to just rely on that.

But it was these experiences that really made me curious about how parents actually have these conversations with their children. What does these conversations look like and how do children respond? And how do parents then respond to how children are responding to those conversations? And so just thinking about what strategies can parents use to support their parenting as they're tackling these issues. So it's those questions that have brought me to the work and keeps me in the work.

EmbraceRace: Can you define racial/ethnic socialization? What are the different strategies that you see or that are in the literature about how parents or caregivers do that?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. So racial socialization is a process used to convey implicit and explicit messages about the meaning of race, and then add in some strategies to cope with racism. And this process can happen in schools, in neighborhoods. And it happens in all families. It just may happen differently. The frequency may be different, the combination of strategies may be different, but it's there. Transmission can happen in various ways. So it can be transmitted verbally, or it can be transmitted non-verbally. Non-verbally, an example of that would be a child may notice how a parent's voice or their posture may change in the presence of someone that is racially different from them, right? The process is also, it could be direct or indirect. So a parent may talk directly to a child about recent protests, but the child may also overhear their parent on the phone talking about the protest. And so then they receive indirect messages that way as well.

And then it's also bi-directional. So children are not just these passive recipients of racial socialization, but they also help shape what that racial socialization may look like. Earlier today, I saw a Facebook video, and I don't know how many others have saw it, but I saw a Facebook video of a four year old Black girl who was getting her hair done by who I am assuming was her mother. And while she's getting her hair done, she turns to the camera and she says, "I'm ugly." And so the mom turns to her, looks her dead in the face, and just filled her with affirmation. She talked about, "Black is beautiful. You have beautiful chocolate skin." And in that moment, the little girl was crying, the mom was crying, I was crying watching the video. But it was an opportunity for this mom to say, "This is happening to my child right now and this is how I'm going to respond to it."

Racial socialization can also be proactive too. Parents can plan to have these conversations. "I'm going to think through what I want to say and when I want to say it." And so it could also be a proactive thing. And so when I'm talking about the different practices that make up racial socialization, there are four different types of strategies or practices.

EmbraceRace: We assume that, especially with the young children, that all the messages they receive come from home or from school because it seems like they're in one or the other place, maybe in preschool. This was clearly a case, almost surely a case where, not to say it didn't come from home, but it almost surely didn't come from her mom, judging by that reaction. That's the thing people really need to take to heart.

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. I think it's really important that we understand when we talk about racial socialization, it's not just something that happens in families. It does happen in schools. It does happen in neighborhoods. You're receiving all kinds of messaging. I go back to when my child, my daughter was three or four years old and how she had just taken a bath and she got out of the bathtub and was boo hoo crying because she wanted to have long blonde hair. I know I didn't provide those messages, and I tried to be really careful in what books she read and what dolls she had. I tried to be careful in that, but she still received some type of message about what beauty means in her eyes.

I think it's really important that we understand when we talk about racial socialization, it's not just something that happens in families. It does happen in schools. It does happen in neighborhoods.

Dalhia Lloyd

EmbraceRace: Right. Which is to say, by the way, racial socialization isn't only about how we come to understand our own identities, how your daughter comes to understand her Blackness if that's how she's identified, but how she understands perhaps Whiteness and long hair, so other people's identities.

Dalhia Lloyd: That's exactly right. So these are the four big types of racial socialization strategies or dimensions that are in the literature. And so I'll go through these really quickly.

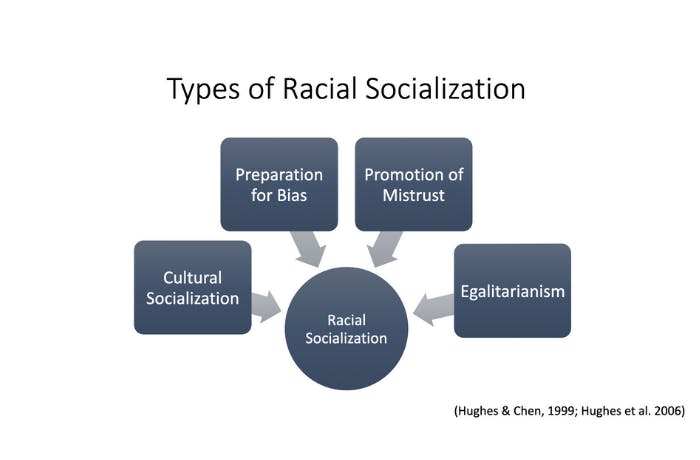

Types of Racial Socialization

- Cultural socialization - Practices that parents engage to teach their children how to navigate cultural spaces and teach cultural pride, like through dance or movement or art.

- Preparation for bias - Practices that parents use to help their children understand what racial bias looks like, and then some strategies to cope with it.

- Promotion of mistrust - Practices parents use to teach their child to be cautious of interracial interactions. Now this strategy is similar to preparation for bias in that it, it prepares for bias, but it differs in that it doesn't provide any type of strategies when faced with a negative racial experience.

- Egalitarianism - Practices that parents employed to teach their children that all people are created equally and that racism is not a problem. An example of egalitarianism is a parent that may encourage individual characteristics without any focus on their child's culture or group membership.

And so those would be the four types of strategies that specific practices would go under in racial socialization. And as I mentioned earlier, these four practices, while they are distinct in their own right, there are moments where they may merge. And so you might have a parent who's practicing cultural socialization and preparation for bias at the same time. So it's not that a parent just practices one of these four things, but there might be some merging going on as well.

EmbraceRace: So forgive me, folks if I'm stating the obvious, but what we're saying is that all parents, all caregivers, in fact, empirically, use combinations of these. And maybe not every single thing that they do, but most of what they do can be grouped under one of these four categories. And then they draw from these four categories and do the work they do with their kids.

Dalhia Lloyd: Absolutely. Absolutely.

EmbraceRace: And Dahlia, they may do it, ideally they're intentional. We also, as parents, socialize unintentionally, right?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yep, absolutely.

EmbraceRace: As you pointed out, there are also families with different identities. Not only racial identities, class identity, different circumstances. So the context in which these strategies are used presumably also has an effect on the impact they make.

What do we know about the effects of racial socialization? What does it mean to use one or the other or different combinations? What does it even mean to be effective?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. So broadly speaking, there are some strategies, such as the promotion of mistrust, that are linked to negative child outcomes, such as increase in behavior issues. But luckily there are some that are linked to positive outcomes, like engaging in cultural socialization has been linked to children having higher self-esteem, higher academic performance and engagement, higher problem solving skills, and a decrease in behavior [issues].

And so some examples of cultural socialization and how to support a child in that would be going to the museum to learn about their history or reading a book that shows the child not just their physical characteristics, but shows their lived experiences as well. They could see themselves in the book. Or attending cultural celebrations, sharing family stories and traditions. These are all things that can help children have a strong racial identity and feel good about themselves.

EmbraceRace: So cultural socialization is sort of cultural empowerment?

Dalhia Lloyd: That's really great. Yeah.

EmbraceRace: So promotion of mistrust can have negative outcomes. What about the effects of egalitarianism?

Dalhia Lloyd: You know what's interesting.

EmbraceRace: We all bleed red, Dalhia.

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. So what's interesting is in the literature there has been some mixed things that come up with egalitarianism at a younger age. Not so much maybe at an older age, but at a younger age there has been some mixed results, but we know that it is important that we help children understand, and not be afraid to have conversations about race and racism. So we also know that children are able to see color. Children are able to see color at infancy, and by three or four, five years old, they're able to use race in a thoughtful manner. And so there is some mixed things out there about how egalitarianism is linked to positive or negative child outcomes. But I think it's really important that we recognize that children are indeed having these conversations, thinking about them, and we, as teachers, as adults, caregivers must be able to help guide those conversations with them.

EmbraceRace: These last 10, 15 years, I'm thinking about the first Black president, Black Lives Matter, Donald Trump, Charlottesville, all of it. George Floyd and the protests last year. And this surge in, especially among White Americans, but not only among White Americans, this greater appreciation for the importance of race. And even as we see some things that would disturb us certainly, you also see a lot more people, including parents, White parents, and all other parents, some larger share of those folks, I think, who are trying to raise their kids to really to value diversity. But even sometimes to go a bit deeper, to tell the story, a more accurate story of racial history, racial inequality, all this stuff.

For those parents then who are saying, "Whatever our identity, well, I want to raise my children to value children who look different than they do. To appreciate the difference not just in how they look, but in their histories of how they're treated in this country and what the present looks like for them."

I don't see that that aligns with any of the four strategies you have described. Does that mean that that has been done so little until now, if now, that it's not recognized as a distinct strand? What do you say about that?

Dalhia Lloyd: That's actually an interesting question because these four dimensions, I call them dimensions, while they are one of the hot topics in the literature, I do argue that there are some other dimensions that maybe research has not tapped into yet. I think about the social justice piece of parent conversation, where does that fit in these four dimensions? And so, yeah, I do agree that there's more to be done in this area. And I think that while people of color typically have had these types of conversations with their children for years and years, I think that the recent events that you've just mentioned has bubbled up some things that now a lot of parents, White parents, are talking about how do I have these conversations with my children? And I think there is a lot more to be done in that area as far as research and figuring out what does that look like? What are those dimensions and strategies and practices, and then how does that relate back to child outcomes?

EmbraceRace: Dalhia, you work with a lot of early childhood educators.

What does this mean for an educator looking at their classroom? What are the approaches that these socialization methods suggest educators should take to affirm all identities in their classrooms?

Dalhia Lloyd: I would say one of the first things is to acknowledge that we in this society live by this construct of race, and to understand what that means for specific populations in your classrooms. I would suggest that teachers not shy away from the conversation. If children are bringing up George Floyd, or even the recent passing of Juneteenth, that these are conversations that you don't shy away from, that you engage in these conversations, and then you help the class with strategies on, how do you become a social justice warrior? How do I stand up for my peer if I see something that is inappropriate or disrespectful? And so I think those are some strategies that teachers can use in their classrooms to help us move the work forward.

EmbraceRace: It seems like it would be important, the way I think about it, to do the cultural socialization or empowerment piece early, early, early, before you're preparing for bias?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah, that is really important. I think, when you think about just these four dimensions, that cultural socialization is one of the pieces that bubbles up for all people of color, that piece is the part that bubbles up in helping children feel confident about who they are in their racial identity. So, yeah, I agree that that part is the most important part.

EmbraceRace: To start with anyway. But through books and bringing in people from the community and that kind of thing. So we're going to bring on a couple of parents as well, to give some different perspectives to the conversation.

EmbraceRace: Keeley and Ben, hello! So Keeley Bibins is a passionate educator. She started as a Pre-K teacher in a predominantly African American Title I school. She's currently an Educational Facilitator for the Buffett Early Childhood Institute where she provides on-site support, professional development coaching to elementary school leaders and teachers Pre-K through third grade. She also works with EmbraceRace quite a bit leading with a co-facilitator the Color-Brave Community. And she's also going to be on a webinar wearing a different hat next time. So you'll hear more about Keeley, but today we're asking her to come on as a mother. And she is the proud mother of three young Black men aged 20 and seven, and two of the three young men are twins. Biracial seven year old twins.

EmbraceRace: And we're so excited to be meeting Ben. Ben Heath is a proud father of two Asian-White children, one of which has Autism. Raising biracial children has opened his eyes to the realities of racial struggle in today's world. He's passionate about advocating for fair treatment for members of all races and those with special needs. He's actively learning about the best ways to explain race to his children as well as having open conversations with them about their races. Welcome Ben and welcome Keeley.

As we heard, their own racial identities of their children are not incidental to how they are trying to raise those kids. We'd love to get a little bit of insight into how you're thinking about that.

Keeley Bibins: Hi. Well, I'm glad to be here with this hat on, to be a parent and to talk about my boys. I will say that my conversations with my children about race has definitely evolved from when my 20 year old was a child versus the two seven year old's, because there's a big gap there if we haven't noticed. And there's a lot of learning between the two.

So as I have listened to Dalhia, this is my second time being able to hear Dalhia's wonderful research in racial socialization, I try to identify what kind of conversations did I have with my son when he was younger about his race? And I think then I was more of that preparation for bias with him because of what I know, and I was a young mother, and he was a young Black man, and some of the experiences that I had growing up as a child and the fact that I even knew that I was having a Black boy, Black man, made me sick. Physically sick when I found out I was having a boy, just because I knew some of the things that had to start preparing him for.

And so the conversations with him were more about preparation for bias. "Know who you are. Be strong. Those kinds of people are going to try to challenge you. Some people are going to try to tell you who you are. Some people are going to try to make you seem less than, and you got to..." So it wasn't this love, it was like, "You need to do this, do that, and be prepared." So the conversation with him was much, much different. Really sending him to school, and even having the conversation with some teachers. I think back about my son, and my son was very young and very articulate very early because I needed him to be able to tell me what happened at school today. "I needed to know what they said to you. What did you say? How did they respond? What did they look like when they said it?" Because I need to know if I need to be his advocate and stand for him. So that's how my 20 year old and our conversations started happening about race.

And then because of my former marriage, his siblings were biracial. So as he got older, we start having different conversations on, "Mommy, why are you not with my dad? Because you both are brown and their mommy is White. And you need to be with my dad." So that started different conversations with, I don't want my son to think it's okay to judge people. Love is love, honey. And so it kind of changed to that, I want to say towards that cultural socialization just a little bit, because I wanted him to understand, be proud of who you are, but that doesn't make you better or make anyone less than you. So that was the reason why we had that conversation with him.

Now, when I acquired the twins, it's a little different because one, as you can see, like I said, there's a gap. 13 years there. So then I had already became a Pre-K teacher. I had learned different trainings. I had my eyes open to different ways children learn, ways children acquire information. I had a classroom of my own, so I'm starting to build a community with different children from diverse backgrounds. So I had a little bit more knowledge and understanding of things when the twins came. And so the twins, we started out with that racial socialization. It was really something about, first of all, who are you? And I think I did it in a kind of lackadaisical way because I was like, "This is who we are, and this is our family, and we all look different, and you all look different."

Keeley Bibins: But there was a time where they said that my twins, even though are biracial, were having racial identity issues. One twin told my older son, because my older son is really chocolate. He's a chocolate, beautiful young man. But anyway, I'm biased. He's a beautiful chocolate young man. But my twin told him, we heard him say, "That's why you're Black." Wait a minute. "Wait, where did that come from?" One thing I did learn is I didn't want to make him feel bad about his comment. Because I know that that can have a very adverse effect of what I wanted.

But I started asking him more questions like, "Tell me more about that. Where did that come from? Why do you feel that way?" And I asked him, I said, "Well, what color are you?" And he was like, "I'm White." "Really?" And people who know me were outside of this conversation, but my niece was like, "Aunt Keeley, what? You minored in Black history, where is this coming from?" And my niece was like, "Oh, that's it. We're doing Black history studies every week until you understand." And I said, "No, we don't want to do that because if we don't do it carefully, we can actually push him in another direction."

So we started to have more conversations. Instead of bringing that back up, about that conversation, I started to be more intentional with the books that he was reading, the books that he was surrounded with, the story time bedtime stories that we were looking at, some of the movies that we were watching as a family. And so I started to be more intentional in setting, kind of like what a Pre-K teacher does, we set the environment so that he can learn from the environment and we can start having those conversations through the environment and allowing him to explore and learn that way, and then keep telling you to have these challenging conversations. So that's kind of how that changed and shifted.

[With my twins,] I started to be more intentional in setting, kind of like what a Pre-K teacher does, we set the environment so that he can learn from the environment and we can start having those conversations through the environment and allowing him to explore and learn that way, and then keep telling you to have these challenging conversations.

Keeley Bibins

EmbraceRace: Let's go to Ben. And Ben, tell us a little bit more about your kids and what's your thinking?

Ben Heath: Yeah, absolutely. So first off, thank you for having me. I'm happy to be here. As a father of two biracial kids it's really important to both me and my wife that we raise our kids to be proud of both of their races. They aren't defined by one or the other. So at our house, that means we have dolls that are different races. We have dolls that look like them. We have Black dolls. We have White dolls. We really make sure that they're able to play with the different races and socialize even through their play, because that's where most of their learning is coming from. And I have a two-year-old and a five-year-old.

So on top of that, when we talk about reading books at night, or with my kids, it's reading books all day to be honest, but we're reading books that have that diverse mix of races and also celebrate their Filipino culture. We want our kids to know that just the way somebody looks or sounds, that doesn't make them wrong. That doesn't make them bad. That just means they're different. They have unique experiences that they can share with them. And we're all people. And first and foremost, that's how we need to be treated.

So from socializing race, I have a couple of examples that just come to mind. The first one is my son. He has Autism. He's been going to Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) for the last two years. It's been hugely effective with him. Applied Behavioral Analysis is a proven methodology that helps reinforce positive behaviors. And it's had a tremendous impact for him. It's all science-based, and it helps him learn the right way to act, the socially acceptable way. We don't roar in our friends' faces, that type of thing.

So he came home when he was about four, and he came up to me and said, "Dad, why is Cameron's skin black?" Which was immediately followed up by, "Why isn't my skin black? I like the way it looks." It gave me a good opportunity to use an analogy he would understand. So one of his favorite cartoons is Pokémon. And we had recently watched an episode where there was a red Pokémon and a blue Pokémon. They were the same type. They just looked different. So once I explained that to him, it was like a light bulb went on. He understood everything was good and we just went on and played.

So that type of conversation, when we talk about seeing no race, we celebrate that races are different and people have different experiences and different history that comes with it. But at the end of the day, they're still people. A little boy is a little boy. A little girl is a little girl. And we can all be friends.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Ben. So Keeley, you have a young Black man in your house, a 20 year old son, who as you say was socialized by you somewhat differently than the way you're socializing your seven year old's, but he's in a position now to support the socialization of his younger siblings, and has been himself sort of politicized in this time, again from Obama, all the things I just mentioned, and now, and I'm wondering how that looks.

Are you and your 20-year-old more or less on the same page on how you practice racial socialization? Are you inclined to have the same kind of conversations with the twins, the seven-year-old twins?

Keeley Bibins: I'm glad you asked that question. We are now. And that's why I think it was important for me to address how different it was with me and my older son, because there was some unlearning and some things I had to mend with him. And then he already had some experiences growing up in school. Because he was in college, and he was one of the young men who was in the back seat who had to be pulled out of the car and sit on the curb and checked his ID when all these kids were just driving to Walmart. And he was with a White friend who was driving, but the rest of the guys were Black.

So I had to start having those mendable conversations with him. I'm still trying to do cultural socialization with him, but it was harder. It's kind of like what Frederick Douglas said, "It's easier to do it right the first time than to fix a broken man." Right? And so me and him had to have some conversations. Like truly, I apologized. I did my best, but then try to get him to have conversations on why I do it differently with the twins, and to help him understand why I do it differently with them. Because now what I learned when I was with him, and I'll talk about it at the next webinar, is what I learned, how I learned about race. Right? And we raise our kids the way we were raised sometimes, until we know better.

And so I was raising him out of that versus I had to unlearn some things. And so I had to explain to him why I don't talk to the twins that way. And so much like, Ben, you're absolutely right. My twins, they don't identify. We did a lot of work, and if you ask them today what race are you, they will say either they're biracial or I'm Black and White. We don't pick one over the other, which is different for me because I'm not, right?

And so I had to actually talk to people who are biracial. I have some cousins who are biracial, some coworkers, and say, "Tell me. I have biracial children. And I need to not teach them how to be Black. I need them to walk in being biracial and that's not my experience." So I had to do some learning and unlearning myself in order to help build them and to surround them.

And they do too, Ben, and my boys are boys and there'll be dads one day, so don't judge, but they have dolls. They have dolls that have multiple nationalities, right? And we have action heroes. But I've purposely looked for books and posters with children that are biracial, books that I was going to put on our Facebook page. I Am Tan is one of our favorites, where this little boy was told he had to choose between if he wanted to identify as Black or White. And someone talked to him like, "No, create your own color. I am Tan." Mixed Me, I Am Mixed, and those books where I'm not just telling them, "You're Black or White. You are in a whole group by yourself. And I mean in a whole separate group, even from your mother and your brother."

EmbraceRace: That's awesome and totally interesting. Just the way we are different parents to each child. Right? And we learn, we know better, we do better. So I love that, Maya Angelou.

Dahlia, can you respond to the Keeley and Ben? What do you hear in what they're saying and how does it aligns with what you hear from parents and teachers and how you think about racial socialization?

Dalhia Lloyd: It's interesting to think about this. The two things that I've picked up on was that I think it's important, especially for teachers to hear this, is that they both have this goal of wanting to have these conversations with their children, but they both approached it differently.

Keeley with her two twins, she talked about the environment and how to set up an environment that gave messages that she wanted her children to have, and the books that she provided. And so she kind of went that route. Whereas, Ben talked about, "I talk to my child in analogies," right? And so for him and his family, that's really important. And so I think it's critical that teachers pick up on those differences and how parents, yes, absolutely want to have these conversations, but how they're doing it is differently. And these are things that you can use in the classroom.

So if you have a conference with Keeley and she talks about setting up her environment, then you ask, "What can I do in my classroom environment to support your work as a parent?" If Ben is talking in a conference about, "I use a lot of analogies." "Tell me more about that. What analogies are you using? What can I use to support your parenting?" And so I think those are a couple of things that I've picked up on that I think would be really interesting for teachers to have conversations with parents about.

EmbraceRace: We have several comments in the chat giving love to Keeley for supporting her boys with dolls. We're all for it. I know Dahlia and Keeley, you both work with parents and educators, so have familiarity with those groups. So certainly would love to hear from both of you.

This is from Nick. Nick says, "As a racialized kindergarten teacher who does anti-racist pedagogy, I believe it's critical for early year educators to share their pedagogy and process with the families of their students. Meaning to provide common vocabulary for discussions at home, at school, to open up a dialogue with parents, with seeking advice, et cetera. Can you speak to this topic for both the educators and family members who are listening?"

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah, I think that it's really important to start with asking parents, "Are you having these conversations at home? And if you are, what does that look like? This is how I plan to have these conversations in my classroom. These are the terms that I'll be using. Do you agree with these terms?" There's so many terms to describe different things. And, for example, I like to get the question of, "Do you prefer Black or African-American?" And for some people, one or the other is what they prefer. Right? And so having these conversations ahead of time so that you are aware of how your parents are wanting to have these conversations is really important.

And not only that, but then parents also understand, "Okay, so as a teacher, I know that my child is going to hear these terms in the classroom, and how do I feel about that? How am I going to support that at home?" So that's how I would respond to that question. I hope that was helpful.

I think that it's really important to start with asking parents, "Are you having these conversations at home? And if you are, what does that look like? This is how I plan to have these conversations in my classroom. These are the terms that I'll be using. Do you agree with these terms?

Dalhia Lloyd

Keeley Bibins: Very similar to what Dahlia was saying, and I can actually go back into my time in the classroom where it's one of those situations. I was in Pre-K, so we actually did home visits, and I was able to ask questions like this. Ask the family questions, like "What is it that you would like to take from your home into our classroom? Does your child have a nickname, what makes them more comfortable?"

But also what we did too, is when we did art and we would talk about people, I made sure that we had color tone markers. We had color tone pencils. If we had crayons, it was skin tone color pencils, skin tone paint, and skin tone paper. We didn't call each other by race, we were not talking about race at the time, but we were definitely talking about putting your hand on the color. "Which one matches you? Which one do you feel matches your skin? So when you draw your self-portrait, which one are you going to use?" Right?

Because I worked at a Title 1 school, in five years, I only had two White students. But I always saw faces. I had always every year between five to seven White faces. So I always invited my parents to come look at this and to use it as a flag to start conversations with their children and how they wanted me to support that in the classroom.

EmbraceRace: I remember when our kids were in preschool, we had a teacher who asked us just the first question at a parent-teacher meeting was, "So how does your family feel in this community? Do you feel like part of the community? How could we facilitate?" And it wasn't a direct race question, but it invited us to talk a lot about our family culture and how we fit and didn't fit. And it was just a lovely start to that relationship, was the suggestion, the question to ask.

Someone asks, "I suspect many parents have heard their child make comments about the color of someone else's skin, or make presumptive comments based on the color of someone else's skin. Can you offer some advice or examples, scripts, of how to use those comments as jumping off points to talk about race and anti-racism? I'm thinking of three to five-year-old's."

And actually, I wanted to ask Ben. You have the youngest kids here, and I wonder if you've already had that experience?

EmbraceRace, Melissa: Ben is the most tired, probably.

Ben Heath: Yeah, absolutely. So there's been multiple times that my son has said things just based on what he notices. Kids between that age are completely honest about everything, and it can be embarrassing sometimes, but it just leads to good conversations. And when he's asked me questions about, "Why does that person look that way," I've always been able to take those and I remove emotion from the conversation, and we just deconstruct what he's talking about. And we talk about, "Oh, well, everybody's different." So I know we were talking about race, but for instance, somebody in a wheelchair. "This person's in a wheelchair. Just because they're disabled, that doesn't make them not a person. It means something happened and they can't walk like you and I." And as soon as we normalize it and level-set the conversation, we move on. It's just an opportunity to have the conversation.

Dalhia Lloyd: And I would add to that, that I think that it's important that parents encourage and allow children to ask more questions and not to shut those questions down. Right? So although you may feel like I've answered this question and I've tried to explain why this person may be different from me or you, the child may have even more questions. And I think it's important that we say just because I had this one conversation doesn't mean that it's going to end. They might go to school the next day and something else comes up. And so they're going to come back and ask you three other questions. And I think it's important that parents stay open and willing to answer those questions.

Keeley Bibins: And one thing I wanted to add to that, too, and to also what Ben was saying, is that one thing I had to do myself and encourage parents to do is take the embarrassment out of it. Right? Because sometimes kids ask questions. Like my son, we were at a restaurant, a man didn't have a leg. Right? And he was 5, 6 at the time. So he's pointing, and I'm like, "Hey, would you like someone to point at you? We don't want to point." So he's like, "Mom, what's going on with his leg?" And I said, "We've already talked about some people have special things and he has a special leg. His leg is not all the way there, so it doesn't look like ours. But he just has a special leg, no different than Mommy's special eyes," because I normally wear glasses.

And so we've always talked about differences and things like that. And he has what is called mastocytosis, so he has these brown bumps. And I'm like, "Would you like someone to point at you for your brown bumps? It's just what makes you different." Right? And so normalizing those conversations and trying to take the embarrassment out of it, because it's a learning opportunity.

And the man did come and compliment on me the way that I explained that to him. But I think that sometimes we as educators and sometimes as parents, we're very "Shush! Don't. We don't want them to hear," because we're so embarrassed, but that actually keeps our kids from wanting to ask questions and learning if we kind of shush them. So like Dahlia said, we encourage them and answer those questions.

Normalizing those conversations and trying to take the embarrassment out of it, because it's a learning opportunity... But I think that sometimes we as educators and sometimes as parents, we're very "Shush! Don't. We don't want them to hear," because we're so embarrassed, but that actually keeps our kids from wanting to ask questions and learning if we kind of shush them.

Keeley Bibins

EmbraceRace: Here's another question that invokes or raises the possibility of shame and really it's one of the questions that we've gotten a lot in different forms over the years.

Someone asks, "How do I instill racial pride about being White in them? The statute for the many White races come from a history of colonialism. I don't want to shy away from sharing this term, but how can we best do that without sparking shame?" Essentially, how do you instill a healthy White identity?

And perhaps, as you said, Keeley, with respect to your biracial and multiracial kids, this is a question from someone who has, they say, biracial kids or part White, and as in your case, more and more parents are hoping that their children will be able to choose for themselves and certainly can embrace, in this case, both parts, both the racial identities.

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. I think oftentimes when we are having conversations around race and how to have these conversations with children or how to have these conversations in the classroom, there's this automatic assumption that this equates to White identity being a bad thing. I think it's important for teachers and parents to understand that what we're talking about when we're talking about anti-racism in the classroom is not to say that White identity is a bad thing. We're talking about and thinking about systematic power and privileges that are at play. So it's okay. We want White children to be proud of who they are. Just like I want a Black child to be proud of who they are. I would hope that a White child doesn't feel embarrassed or shamed or wish differently about their skin color.

Just like I wouldn't want that for a child of color. And I think that by acknowledging that race is a social construct, talking about the status quo is having in America, but that we all contribute to what is America. I think that may help with White children in racial identity. And I go back to that cultural socialization piece while it is really prevalent in families of color, I think it's also important in White families too. We have the history. But being able to talk about the real history and not sugar coat it, but letting children know, yes, this is what happened in our history and this is how we want to move forward. So not ignoring things, but actually putting it out there and talking about it.

I think that by acknowledging that race is a social construct, talking about the status quo is having in America, but that we all contribute to what is America. I think that may help with White children in racial identity... Being able to talk about the real history and not sugar coat it, but letting children know, yes, this is what happened in our history and this is how we want to move forward.

Dalhia Lloyd

EmbraceRace: And we do have choices in how we show up, right?

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. Yep. Absolutely.

EmbraceRace: I see that in Louise Derman-Sparks as well. And I always refer to her book, when people asked us, What If All the Kids Are White? in the classroom and what you'd do. And White, as you were saying, it's a construct. But those of us who are White, in my case, it's French Canadian. And there's a history there and there's not great things done and great things done. And there are individuals we can point to who were on the right side with justice just as there are today.

So that question always surprises me, "How do we raise White kids to be proud?" Because there are a lot of examples that we should just unearth of people also doing great things and again looking at those specific histories as opposed to "White." White as something that's supposed to divide us is the construct.

EmbraceRace: Dalhia, do you think there are interactions or intersection points between cultural socialization and social justice dimensions?

Dalhia Lloyd: Absolutely. So for me, from a social justice perspective, if I am taking my child to a protest, probably they're going to see signs that talk about, I'm going to say from a Black perspective, they're going to see signs that talk about Black Lives Matter. They're going to see signs that talk about Black is Beautiful. And so those are some cultural socialization messages that they're getting while at this protest. And so that's how I see it emerging.

But then I also think that there's this piece where affirming someone's racial identity gives them the courage to speak up. And so if I feel comfortable in who I am, then I'm more likely to not be afraid or shy away from having conversations about race and racism. And I hope that as I've raised my children, that I've planted those seeds in them through some cultural socialization that I'm confident in who I am. I'm confident in the things that I do and when I'm faced with a bias, I'm going to rely on those and challenge some of those biases.

EmbraceRace: Someone asks, "How does one balance the desire to offer very young children a positive sense of racial and cultural identity and positive views of diversity with the need to begin to talk about prejudice, colorism, bullying, and racism?"

Now we talked earlier about a sequencing of things. Cultural socialization, cultural affirmation, affirmation of identity. Hopefully bolstering our young people, perhaps do that very, very early before we dive deep into really harder things that might otherwise make the child feel threatened, isolated, at risk. And I wonder, we also know that there will be a lot of people who are watching or not watching who will see this at some point, who will say, my child is 5, 7, 12, and I haven't actually done that work.

And that, by the way, includes children of color. Or parents to children of color, who haven't done that work necessarily, or to the extent that they might've done. And Ben, I'm looking at you too. So we know of course, just in the last year, not only George Floyd's murder, murder of Asian American folks in Atlanta and a lot of harassment of Asian Americans.

So what do you do? What do you say to those parents who say, "Gosh, I haven't done that work, or I'm not confident that I've done it enough." And yet this thing is in the news. What do I say to my five year old or my seven year old? When, again, I haven't done the work, but this is happening. And even if I don't say it I'm concerned that he, she, they may hear from others and be exposed.

Keeley Bibins: Sure. That's a really good question and something has been posed to me working in one of the schools and one of the community volunteers said something that was very, very eye-opening for me is when he said, "Before we get to talk about racism, this is already happening, but we also got to build their own confidence within themselves." And this is in a school that goes up to sixth grade. So even though we might have kids who may not have had that conversation, it's time to surround them with people who they feel supported by to, even if they can create a space where you can talk about whatever's on your heart, and we can have a relationship to the point where even if something scary does happen, or they run into something like watching this, they can bring that to someone, whether it be at school or a parent, and they will address those fears and have those conversations, but still at the same time, build that child up and secure them in who they are.

I think this is where that school parent partnership really comes in because that child is really going to need some really strong supports around them, whether they go home and be supported and have that person to say, "This is how I'm feeling." And "It's okay not to be okay, and I'm here," or they go to school and they have that same person. But at the same time, we're building, "Yes, but that doesn't take away from you being strong. It's all about people making choices. It's not everybody, unfortunately this is happening in our country." And then asking them, "What do you think about it?" And really helping them process through what's happening around them.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Keeley.

Ben, your children are very young. I think you said the older one was almost five. Have you and your partner said anything about the harassment, ill treatment, violence, directed against Asian Americans?

Ben Heath: So we've had a lot of conversations between my wife and I, which means that my kids have gotten it through proxy, but we haven't had those direct conversations. And I'm listening to this question and I'm listening to Keeley. And I think now is the perfect time to have that talk. The opportunity is there, and it's never too late to start talking about it. As Keeley said, it's all about having a safe place. A safe place to have the conversations and whether that's home or school. But I would hope that home is going to be a place where my kids always feel safe. And where we can talk about whatever we need to. So with my five-year-old getting ready to start kindergarten in a couple of weeks, we've been thinking about how do we go from what we've been talking about, where getting him to accept all races, to now he's going into kindergarten where he'll deal with the question my wife did, which is "What are you?" And give him the confidence to answer that question and also be ready for any bullying that might happen.

EmbraceRace: Ben, thank you. I have to tell you, you not only look like your mom, but you have her speech patterns, which is cracking me up right now. And Dalhia, I'll give you the last word.

Dalhia Lloyd: Yeah. I would say Dr. Anderson, who's been on with you before, Dr. Anderson and colleagues have talked about there are three things that you can really do. One, provide a space for children to talk about race and racism. But two, practice. So maybe you practice in a mirror, maybe you practice with a colleague or a friend or your partner. But practice how you're going to have those conversations so that you have time to think through or stumble through how you want to approach those conversations. And then relying on those two so that you don't create a more stressful situation when you're with your child. And you're engaging in these conversations. It's already stressful to talk about race and racism. And so you want to try to make it as less stressful for you and the child as possible. And so just maybe doing those two things might be helpful.

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much. Thank you everyone who's participating in the chat and to our guests, we'll send everyone the video tomorrow and the transcript will come and we'll let you know about the upcoming webinar that Keeley is going to be in about the self-work. And Ben's mom, Darcy. So you can see if the speech patterns are the same.

So Keeley, Ben, and Dalhia, thank you so much. We really appreciate it. Thank you so much. It was so great. Keep doing the work, y'all.

Keeley Bibins: Thank you.

Dalhia Lloyd: Thank you.

Dalhia Lloyd

Keeley Bibins

Ben Heath

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe