"Ive Never Had A White Baby Before..."

By Megan Dowd Lambert

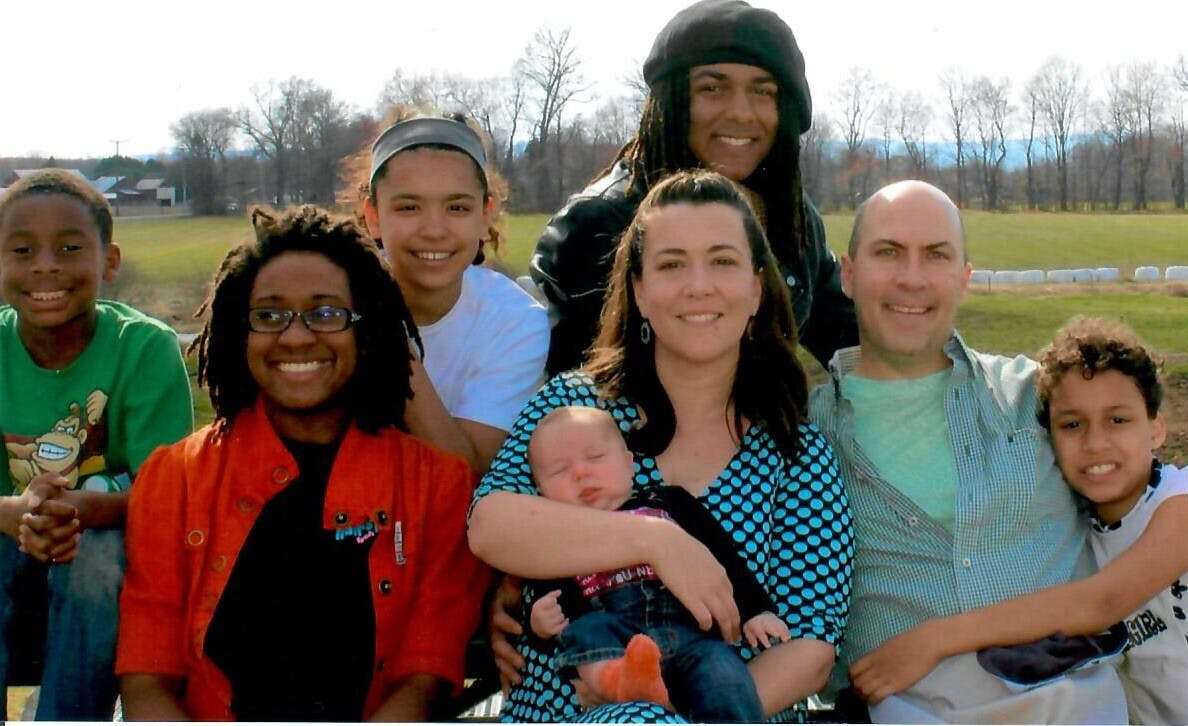

The author and her family

EmbraceRace wanted to know the difference that racial difference makes within families. We reached out to people with one or more siblings whose racial identity(ies) was different than their own or from each other’s. We also reached out to people with kids whose racial identities differed from each other.

We asked them not to write only about racialized differences in treatment, but also to share insights about how those differences in treatment have shaped how they think about race, family, privilege, personal identity, and more.

When I was pregnant with my first child, Rory, twenty years ago, I was sure I was having a girl. My 20-week sonogram indicated otherwise.

“It’s a boy!” the technician said cheerfully, and my first thought was,

“But I’m a woman….”

It was a moment of cognitive dissonance that flew in the face of my obvious awareness that women (even Smith-College-educated, self-described feminists like me) do give birth to baby boys, and it later struck me as quite funny as I thought about the challenges and opportunities of raising a son to be a good man.

I had a similar revelation of the obvious soon after I became pregnant with my youngest son, Jesse, now 19-months old, but this one had to do with race. Rory has Jamaican heritage from his father and identifies as Black or biracial, and my other four kids came home to our family through foster-adoption and are all people of color. My husband, Sean (a never-married bachelor with no children until he met me and my children almost four years ago) is White. I am White, too, and, so it followed that my biological baby with Sean would be White, as well.

“I’ve never had a White baby before…” I thought to myself with some bafflement in the summer of 2014 soon after reading the positive pregnancy results.

This realization struck Rory, too.

“Congratulations on your first Caucasian child,” he said with a laugh when Sean and I told him he was going to have another younger sibling in the family.

I laughed in return and responded, “Well, it’s not really a point of achievement, but of heredity."

Would healthy racial identity development and strong adoptive family bonds be undermined by the arrival of a baby who would be my biological child and would also share my racial identity?

The author with her first adopted child, Emilia, when she was a baby

Although my husband and I were thrilled about the pregnancy, Rory was preoccupied with getting ready to leave for college, and my other children were ambivalent, at best. They voiced concerns about sharing their home with a crying baby in stinky diapers who would “get into everything.” We assured them they would not have to change diapers, and that, no, babies do not usually cry “all the time.” We reminded them that their bedrooms with their things are on the top floor of the house, while the baby would be on the first floor with us.

Some well-meaning people in our lives raised bigger-picture, deeper concerns and wondered if my children, and especially my adopted son and daughters, could end up feeling second-best. Would healthy racial identity development and strong adoptive family bonds be undermined by the arrival of a baby who would be my biological child and would also share my racial identity? How could my husband and I ensure that this would not be the case? Since these concerns came from a place of real love for my children, I listened to them and I incorporated some of their sentiments into conversations I had with my kids about the impending arrival of their baby brother.

I told them that although our household is a busy one, I truly believe that love isn’t something that gets used up, but that grows through sharing it, and I affirmed their rightful places in our family.

“Rory isn’t adopted and he’s the one who pushes your mad buttons the most,” said my daughter, Caroline, “so I know you won’t love the baby more than us.” As hard as butting heads with my teenaged son could be, I glimpsed a silver lining in the way Caroline read our sometimes fractious dynamic as proof that my love for my kids isn’t determined by biological ties.

But Rory is Black. Would bringing a white baby brother into their lives shake my children’s sense of my love for them or of belonging in our family, as some thought could happen? One way I resisted that possibility was to involve them in preparations for the baby’s birth so that they would feel connected, rather than pushed aside, for any reason. I let them be the ones to tell important people in their lives about the pregnancy. I took them shopping so they could choose items for the layette. And when I firmly rejected their name of choice for the baby, Bob, I acquiesced to letting them use it as a name for my belly. But, I also pulled back from making my pregnancy and the soon-to-arrive baby take over our lives before he was even born. Sometimes they just didn’t want to talk about the baby, and so we didn’t.

While I reject the notion that any family’s story, including mine, is a tidy happily-ever-after tale, I daily see how my children’s love for their baby brother can serve as an affirmation of their faith in my own non-biologically driven love for them.

The author’s four adopted children meet their newborn baby brother in the hospital.

When Jesse was born, my children came to visit us in the hospital, and any worry I’d had about his birth causing them a sense of displacement or creating a rupture in our family dissipated. I watched my oldest daughter, Tayja, then sixteen, take Jesse in her arms and fall in love with him, and I remembered the moment I met her when she was seven-years-old.

“You came bouncing around the corner in the social worker’s office, and it was like a light switch went on in my heart,” I’ve told her. It was a moment of recognition that I will never forget even though I’ve failed to find a more precise way to describe it in words. I saw that same sort of light switch on in her as she held Jesse, and I watched her younger siblings step into its glow and follow her lead.

And as focused as he was on college plans, Rory also came to love his baby brother. On the day we moved him into his dorm he paused in his excitement to voice sorrow over missing out on seeing Jesse grow up and made it sound like he was leaving for another country rather than the other side of the state.

Ultimately, Jesse’s birth into our family has made him a site of bonding and love for my children. Instead of making them feel second-best, their relationships with him seem to have strengthened their bonds with me and their stepfather, and with one another, too. A couple of them have very different personalities and are like oil and water in their interactions about, well, nearly everything, and it sometimes seems like the only thing they agree on is that Jesse is adorable. With the exception of Rory, they aren’t biologically related to him, but their love for him is real and whole.

“Where’s my baby?” Emilia asks if she doesn’t immediately see Jesse when she comes home from school.

“Do you mean MY baby?” is Tayja’s standard rejoinder.

“He’s-my-baby”-“No-he’s-MY-baby,” has become a frequent call and response refrain in good-spirited teasing at our house, and when I hear it I sense a transcendence of both biology and race as determinants of familial love. While I reject the notion that any family’s story, including mine, is a tidy happily-ever-after tale, I daily see how my children’s love for their baby brother can serve as an affirmation of their faith in my own non-biologically driven love for them.

While my kids (so far) haven’t had much to say about their racial differences from Jesse, I’m listening, and I’ve thought a lot about how his worldview will be impacted and enriched by the fact that his siblings are people of color.

Sibling #6, Baby Jesse

And then there’s Jesse’s love for them. While my kids (so far) haven’t had much to say about their racial differences from Jesse, I’m listening, and I’ve thought a lot about how his worldview will be impacted and enriched by the fact that his siblings are people of color. The children he loves best in the world are Black and Latina. His everyday reality is one in which he is immersed in reciprocal love with them, and I know that this will inform his racial identity development as he grows into awareness of the privilege he’s afforded as a White boy growing up in American society with all of its intersecting systems of power and oppression.

When I recently asked Rory if he calls or considers himself a feminist, his response was immediate:

“Absolutely!”

With this conviction Rory provides a model for his younger brothers to emulate. My husband and I are dedicated to similarly modeling an anti-racist White racial identity for Jesse as he grows up loving and being loved by his five Black and Latina brothers and sisters.

Megan Dowd Lambert

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe