Reading Mike Jung's "Unidentified Suburban Object" With my Kids, Part I

By Megan Dowd Lambert

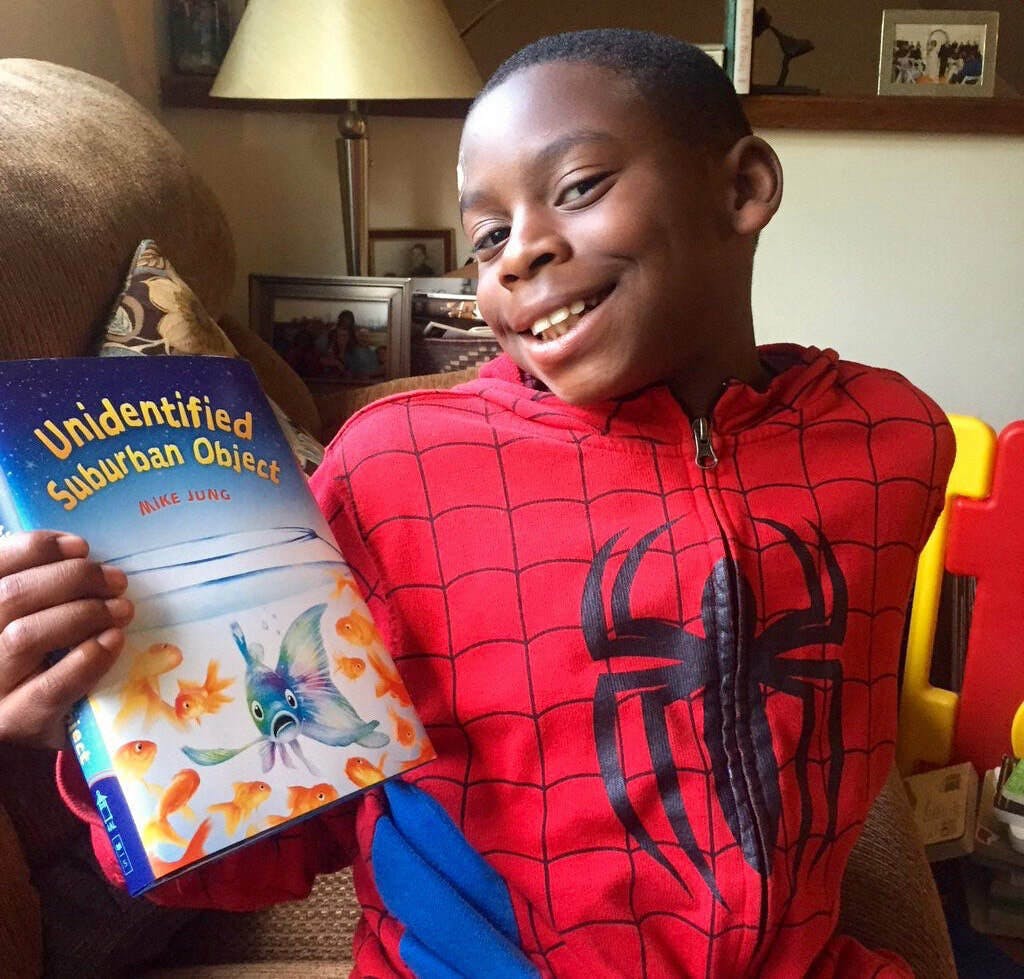

The author’s 11-year-old son Stevie with Mike Jung’s novel "Unidentified Suburban Object." Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

When I started hearing buzz about Mike Jung’s middle-grade novel, Unidentified Suburban Object, I moved it to the top of my list of books to read with my eleven- and ten-year-old children, Stevie and Caroline. It ended up giving us one of the most meaningful shared readings I’ve ever had as a mom. A favorite moment occurred at the big reveal (spoiler alert) when middle-school-aged protagonist Chloe Cho discovers that her parents did not emigrate to the United States from Korea as they’d always told her; they escaped from a doomed planet and are … aliens. When I read the scene with Chloe’s revelation about her extraterrestrial heritage with my kids, Stevie shook his head back and forth as if rattling his brain around in his skull and said:“Wait. What?! Really? They’re really ALIENS?”

“So SHE’S an alien too!?” asked Caroline.

They were riveted.

I hope a lot of kids will get to discover this plot twist on their own, but even if they know about it before reading it for themselves, there’s much more to be savored and appreciated about Jung’s book beyond its stunning reveal. For one thing, it includes some of the most fearless and seamless accounts of a child of color confronting race-based microaggressions that I’ve ever encountered. The novel’s intertwining of its science fiction elements and this stark realism provided my kids and me with a story that was both entertaining and great fodder for conversation about their lives.

I am white and five of my six children, including Stevie and Caroline, are children of color. Over the years they’ve all encountered hurts and indignities arising from others’ careless language, ignorance, or in some cases, blatant racism. I know I cannot totally shield them from racism, and the core of preparing them to confront it is to instill and nurture pride in their heritage and resistance to those who would seek to undermine it. Just the other day in the context of a conversation about the presidential election and how Trump’s candidacy is revealing racism in our country, I said to my 12-year old Latina daughter, Emilia:

“You know that all of this racism says nothing true about you or any other Latino person, right? It says something about the person speaking the racist comments and the culture that supports them. It says they are hateful and ignorant.”

“Yeah, I know,” she said, and the weariness in her voice bespoke the truism that innocence is the domain of the privileged.

I also know that I need to help my children heal from hurts and prepare them to respond to racism in ways that will promote their own safety and personal well-being. Conversations to these ends happen regularly — sometimes preemptively and sometimes in reaction to circumstances in their lives — and reading about Chloe’s righteous indignation and empowered responses to others’ assumptions, slights, and wrongdoing in Jung’s novel was another opportunity for us to talk about how they confront similar situations.

“That was so RUDE!” Caroline exclaimed when Chloe blew up at a teacher after enduring his unrelenting comparisons of her to a famous Korean-American musical prodigy.

“Yeah, but he was rude, too,” said Stevie, and there was a certain admiration in his voice for Chloe and her fearless, outspoken response.

“True!” said Caroline. “Keep reading, Mom-Mom.” And I did.

I've read some online reviews calling Chloe Cho “unlikeable,” but I love her to death. When Stevie and Caroline cheered her on, not despite her sharps edges and fierce resolve but because of them, I said a silent thanks to Mike Jung for giving them this spirited protagonist. Do I want my kids to be rude? No. Do I hope they will respond to others with patience, compassion, dignity, openness, and curiosity? Yes. Do I realize that the stakes are high for kids of color speaking out against authority?

Absolutely. I carry all of these convictions with me as I center a primary concern for my children’s wholeness, and not for protecting the feelings of others who confront them with insensitivity or worse.

The author’s daughter Caroline as a kindergartener in 2011. Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

My kids are not Asian. Stevie is African American, with dark brown skin and eyes, and tightly kinky, dark hair that he likes to keep very short. Caroline is biracial, with African American and Irish American heritage. Her skin is a lighter-shade of brown than Stevie’s, her eyes are dark brown, and her hair is curly and naturally brown, though she likes to dye it. As of this writing it’s cut in a mohawk-style with the center, longer section dyed a reddish tint. Caroline’s appearance often provokes others to comment on her fashion sense and her gender-bending presentation. After she campaigned successfully to get her first mohawk hairdo when she entered kindergarten, I told her to expect comments and questions.“If someone says something about your hair, how will you respond?”

“If it’s a nice thing I’ll say ‘Thanks. I like your hair too.’ If it’s not nice I’ll say, ‘You hurt my feelings when you said that.’”

It was a start.

Soon after the start of school my mother was with her at a local playground and a little girl asked Caroline, “Are you a boy or a girl?”

She responded, “A girl.”

“Then why does your hair look like that?” the girl followed up, and Caroline paused, not sure what to say.

My mother piped up and said, “Because she’s a rock star!”

Affirmed, Caroline beamed and said, “Yeah. I just like my hair like this.”

“Oh, that’s nice,” said the girl. “Do you want to play with me?”

And off they went. This was a pretty ideal exchange, and it wasn’t an instance of race-based microaggression; although it could have veered into territory in which Caroline’s gender nonconformity was not just the subject of friendly curiosity but of scrutiny or degradation, the other girl was open and kind, and Caroline felt supported by her grandmother and able to confidently assert herself as a rock star and a girl who liked what she liked.

I recently used this story to talk with her about another sort of question she might encounter as a biracial person whom others often struggle to identify in terms of race or ethnicity.

“Remember when that little girl asked if you were a girl or a boy and Linney (my kids’ name for their grandmother) said ‘she’s a rock star?’”

“Yeah.”

“Has anyone ever just asked you ‘what are you?’” I asked her.

“What do you mean?” she replied.

“Like when they are trying to figure out more about you? Like your race?”

“I don’t know. If anyone asked me ‘what are you?’ I think I’d just say I am a girl who’s nine.”

“What would you say about your race? Would you say African American, or Black, or brown, or biracial or something else?”

“I’d say I’m African American. But ‘what are you?’ is a weird question.”

When I asked Emilia, about how she responds to this question, which I knew she had heard before, she said,

“I just say, ‘Ummm, I’m a person.’”

“Fair enough,” I said. “But do you ever say you’re Puerto Rican or Latina?”

“Sometimes,” Emilia responded. “But sometimes I don’t want to.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because it’s weird when people say ‘what are you?’”

There it is again: “weird.” I think both girls’ resistance to this careless but common question with the comment that it’s “weird” is a way of calling out how it makes them feel othered — in other words, how it functions as a microagression. I want my kids to be able to respond to such queries in ways that make them feel less like unidentified objects and more like empowered kids of color a la Chloe Cho. That means I can support their matter-of-fact responses about heritage, but I can also support Emilia’s decision to clap back with the statement, “I’m a person.”

Full jacket from Mike Jung’s novel Unidentified Suburban Object Arthur A. Levine Books, Scholastic 2016 Source: http://www.carollydesign.com/unidentifiedsuburbanobject/

We’ve also talked about Mother in the Mix’s “ask-back” strategy which levels the conversation, asserting the position of both parties to a conversation as subjects able to offer questions and not just objects of curiosity. Indeed, one of the reasons that Mike Jung’s science fiction character Chloe Cho is so devastated when she learns that she is not Korean American, but an alien, is that she has lost a key part of her identity, and therefore her subjectivity. Furthermore, she can’t share what she now knows about the story of her family’s history with anyone and she has countless unanswered questions. These facets of her story were fodder for other conversations with my kids that I will recount in my next piece for EmbraceRace. Need something to read in the meantime?

Megan Dowd Lambert

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe