Nurturing Resilience & Joy in/among Young BIPOC Children, Part 1

US society is too often unkind to Black and Indigenous children and children of color (BIPOC children), raising the risk that these children learn to be unkind to themselves and each other. If we are to raise a generation of BIPOC children who fully recognize their own humanity, and that of their peers within and across lines of race and ethnicity, we need the entire village involved: aunts, uncles, and grandparents; mentors and coaches; children's book authors and publishers; toy manufacturers; television and film, and video producers. And more.

The roles and responsibilities of parents, caregivers and educators are especially crucial for our youngest children. In this conversation we focused on the role of parents and caregivers and asked:

- What are the big challenges parents and caregivers must meet if we are to nurture young children who are resilient, joyful and recognize each other's full humanity?

- What tools, resources, and community do we need to help meet those challenges?

For Part 2 of this conversation, we asked the same questions but focused on the role of educators.

EmbraceRace, Andrew: Almost all of our webinars are really about giving you information, giving you recommendations that will help in your caregiving practice, whether you're a parent, you're a teacher, you're an aunt/an uncle, grandparent, mentor, coach, whatever you may be and the truth is that most adults play some sort of role in the life of at least one child.

This one is a little bit different because in this webinar we're actually looking to get information to inform our practice, right? To inform what EmbraceRace offers. EmbraceRace is about, we talk about supporting parents and teachers and other adults to raise children who are thoughtful, informed, and brave about race. We're about providing the resources and the community so that adults, including ourselves, can do that work well.

In doing that, we're usually focusing on adults in the lives of children from middle school and younger, so 12, 13 years old and younger, birth through 13, but, of course, that's a huge population and there are lots of populations within that, right? One of the subgroups we want to focus on tonight are young children, birth through eight, early childhood, and children of color, specifically, Black, Indigenous children and children of color, Latinx kids, Asian American kids, multiracial kids and so on.

That's actually a thing we want to focus on this evening and it's not only about how those children, let's say broadly children of color, see themselves and as we put it in the introduction, in the write up of this session, how do we encourage them to be resilient and joyful? Not only that but how do we encourage them to see each other in healthy ways? Because it's true that if children of color are in a society that often doesn't treat children of color very well, it means that not only will children of color often have a difficult time seeing themselves in healthy favorable ways, being resilient and joyful, but they may have trouble seeing other children of color across racial/ethnic lines, and even within them, seeing them well. That's what today's session is about and it's about hearing from you and hearing from our guests about how EmbraceRace can do more, can do better to serve those of us who care for Black, Indigenous children and children of color.

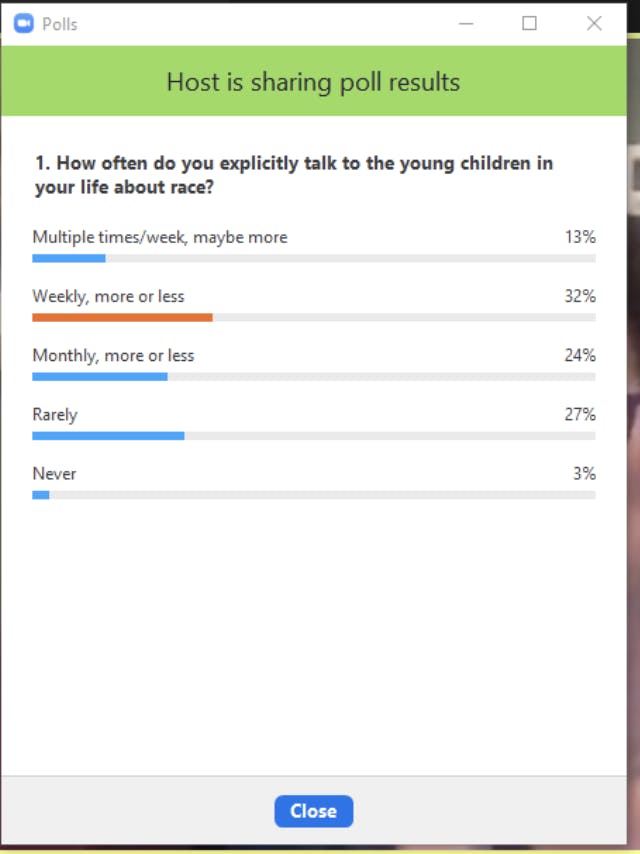

EmbraceRace, Melissa: We're going to start with a couple polls and then we're going to introduce our guests, who have a lot to say, a lot of experience and expertise in this area, so lots to share just as we hope you share. The first one, how often do you explicitly talk to the young children in your life about race? Multiple times a week, maybe more weekly, monthly, rarely, never. Please take that poll.

13% of you said multiple times a week or maybe more. The most common answer was weekly, more or less. About 25% for monthly and rarely. And 3% for never.

We know that's honest. Thank you for that.

Poll two, what barriers do you face in talking to children about race? This one I believe you can choose as many that apply. The options are they're too young, zero to four. They're too young, five to eight. They haven't asked any questions yet, I don't know what to say, other.

Now it may be that you do talk to your children, right? Many of you do, at least sometimes, talk to your children about race but insofar as even if you do, there's some sort of barrier, there's some sort of hesitation, some tension. Why is that? “Other” was the single most popular answer. A third of you said, I don't know what to say. Feel free to put in the chat, those of you who said other, would love to hear if you're willing to share, what some of those other reasons might be.

Now I'm going to introduce our guests, who we're very excited to have on.

Dolores Sosa Green of the Center for Transforming Lives

Our first guest is Dolores Sosa Green. She hails from the Dallas area. Hi, Dolores. She serves as the Chief Program Officer of the Center For Transforming Lives. That’s a great name. She oversees comprehensive homeless services, early childhood education, clinical services and economic mobility services, programs that work side by side with women and their children to disrupt the cycle of poverty in the Dallas area. As the first in her family to earn a high school diploma, a Bachelor’s degree, and a Graduate degree, Dolores believes in and advocates for equity and education. She is happily married to her husband Anthony. She is the mother of two beautiful daughters, Lauren and Maya. Dolores, welcome.

Dolores Sosa Green: Thank you for having me.

EmbraceRace: We are so excited to have you.

Brigitte Vittrup, Professor of Child Development at Texas Woman's University

We also have Brigitte Vittrup. Those of you who have been long time participants in these webinars might know Brigitte. She is a professor of child development at Texas Women's University where she teaches courses in child development, research methods, and statistics. She holds a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin in developmental psychology and her research focuses on children's racial attitudes, parents' racial socialization practices and media influences on children. Brigitte also has two lovely children and is also based in Texas.

We're really glad to have you both. We'd like to start where we always start. In this webinar we're talking about promoting resilience, joy, and anti-racism among children of color.

Dolores, what is your personal investment is in this topic?

Dolores Sosa Green: Sure. I am a Mexican American woman married to an African American man. We have biracial children. We always say they're Black Mexicans. That's the best way to describe my children to give them something. My investment started with my children, especially my oldest who was uncomfortable in her own skin and I didn't realize that until maybe first grade, kindergarten when she came home one day and asked me if I would be the one to pick her up from school.

I share that because my husband would go and pick her up and I didn't realize how uncomfortable she was that her dad was picking her up because of what the other kids were saying. It was a predominantly Hispanic school. There was still a mixture but there was predominantly Hispanic children. It broke my heart. I mean, it literally crushed my heart to hear her and feel embarrassed to have her dad pick her up. I had to have a conversation with her about that, the color of his skin doesn't matter. It was his character. He was a good dad, he was a good provider, he did whatever he needed to do for her. It really made her think. I said, “You should be proud of your skin color, your beautiful Brown skin and his Brown skin. He's a good person. You're a good person. That should not matter.”

That's where it all started. I'm really glad that I caught it with her because then I was able to teach my second child a little bit better. You make errors with the first one and then you get a little bit better with the second one or sometimes reverse, it depends on the parent. From then on, I had to make sure that we had regular conversations about race. Obviously, age appropriate. The best that I could do as a mom because, obviously, I was new to this, having been raised in a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood and not seeing anyone outside of my race in my neighborhood and being taught stereotypes. Yeah. I'm invested because of my kids.

EmbraceRace: That's a really powerful story and I'm sure one that a lot of people on the webinar can relate to. We often feel like we're failing as parents because the environment can be so toxic racially and otherwise but they come back around, don't they, Dolores? They come back around?

Dolores Sosa Green: They do.

EmbraceRace: Brigitte, how about you? What's your investment in this work?

Brigitte Vittrup: Ever since graduate school, the topic of children's racial attitudes, media influences on children's racial attitudes and parents' racial socialization practices, although mostly in White families, has been something I've studied. I also am married to a Black man and so I have two biracial children. They are now 8 and 12 and I have noticed along the way how they talk about themselves. One thing that I've struggled with is that my daughter, because her hair is very different from mine, my hair is blonde and straight and long, and she has very curly hair, very fine hair, and so she has at times brought up how, "I want hair like Mommy. I want hair like Mommy" which is difficult because I've also had to learn how to do her hair.

One time, we were at a birthday party and it was one of those little spa days for little girls and so they all got to make little face masks and oatmeal masks and they got to put robes on and make soaps. Then they had somebody braid the hair and put sparkles in their hair and she didn't do anything to my daughter's hair. My daughter noticed how she would take the other girl's hair, they would do stuff with and braid them, and with her she just put little sparkles on it and didn't do anything. It completely changed her. She just sat over in the corner and she didn't want to do anything anymore because it was so obvious to her how she was different because of her hair. Having talked to one of my coworkers who used to wear her hair straight, she's a Black woman, and she decided to wear her hair natural when her daughter was little. As a White person with super straight hair, it's something I can't do. That's one of the things that I'm having to pay attention to how we talk about our hair and what we expose her to in order for her to feel good about herself.

EmbraceRace: Wow. Getting a lot of comments in the chat. People are really feeling your stories. Thank you both for sharing that. I'm seeing people who choose “other” as a barrier for talking about race writing in. A lot of people named other adults essentially as the barriers. Educators saying that they'd love to talk more to the children in their classes but parents often kick up a big fuss. We have a grandparent who is saying the parents of her grandchildren are the ones who erect an obstacle to talking more about race, which we've found that so often that children are often happy to have the conversation. It is adults who are often erecting those barriers.

Clearly, you are both parents and parents who are, again, as you've said so well, very invested in this issue of how are your children raised, what kind of racial identities do they have, are those healthy identities? Again, we speak about resilience and joy.

Looking at your own children, and thinking about the young children in your lives now, how do you know that things are going more or less well?

Brigitte Vittrup: I think for one thing, I try to listen to how they talk about themselves, how they interact with other people, especially in the environments when they're with different groups of people, are they acting like themselves? Are they acting with confidence? Do they act differently in different environments? I try to pick up on that. I think kids really look around themselves and I think it's really important for them to see themselves in others and see others that look like them. I know when my son had started kindergarten, it was a couple of weeks into it and he used to be really shy but I noticed he kept talking about this one kid, this kid named Omarion. “Omarion was playing basketball at recess and Omarion was wearing Nike shoes today,” and it was just, “Omarion this, Omarion that.” I finally asked, I said, "Who is this kid? Tell me about this kid Omarion." He goes, "Well, he kind of looks like me." That was the first thing, the way he described him, that here was this kid, and come to find out later on actually, this kid's dad ended up being his basketball coach, but he had a Black dad and a White mom and so it was just very powerful seeing how he talked about himself.

Also, my daughter when she's talking about her hair like that is sort of a cause for concern and a need for intervention. At another time, when my son was younger he mentioned that somebody at school had said that he was Black and he goes, "I'm not Black. I'm tan." He's 12 now and he refers to himself as mixed but I think any time if they come up with descriptions about themselves like that that are positive. He was perfectly fine. He wanted to be tan. That's how he saw himself. Then I found just recently actually there's a book out called I Am Tan. I think especially how they talk about themselves and how they act around others is important to pay attention to.

I try to listen to how they talk about themselves, how they interact with other people, especially in the environments when they're with different groups of people, are they acting like themselves? Are they acting with confidence? Do they act differently in different environments?... I think especially how they talk about themselves and how they act around others is important to pay attention to.

Brigitte Vittrup, Professor at Texas Woman's University

EmbraceRace: Thank you. Dolores, how about you?

Dolores Sosa Green: Yeah. My two daughters, they're grown now. One's actually in Minnesota. I saw somebody from Minnesota as a guest. I'm not a perfect parent but I did try to make sure that I talked to my children. Whenever my daughters would say things about the other kids in school or I would pay attention. Because I was aware, because of my oldest, of her experience with her classmates about her dad. With my second one, I made sure that I talked to her about how beautiful she was and that she and her sister were different shades, but they were still both Mexican and Black. I made sure that they understood they should never ignore neither race, neither ethnicity, that they are both.

One thing about my youngest daughter, when she was in the fourth grade, I knew that I had done a pretty good job of talking about feeling confident about who you are, doesn't matter what color you are, what race you are, you could be purple, red, green. It didn't matter. Character matters. The way you treat people matters. All of that matters. Her friends, who are predominantly Hispanic, Mexican American, one of the little girls made a comment to my daughter Maya and said, “Maya is lighter. Maya looks a little more Hispanic than she does Black.” My oldest child actually looks Asian, not even Black or Mexican. But because Maya was lighter and she looks more Hispanic, they forgot that she's Black so they made a comment and said, "We don't really like Black people because of X, Y, and Z." They were stereotyping. She stopped them. She came home and told me about it. She goes, "Mom, I stopped them and I told them that they offended me. I told them that they insulted me and my dad and my grandma, my nana, because I'm Black." I go, "What did they say?" “They got quiet and they stopped talking about it.” I said, "Okay, well, I think you did the right thing." She stood up for herself. She defended herself. That just made me so proud. So proud. She was maybe in second or third grade.

EmbraceRace: Wow.

Dolores Sosa Green: She was still a little girl.

EmbraceRace: It's very impressive. Yeah. She's a quiet child. She doesn't talk. She's very reserved, very quiet. She took after me when I was that age. I was just proud of that. They loved their hair. My oldest has more coarse hair than my youngest but she loves her hair. She'll just flip it and do whatever and do whatever she needs to do, grow it out. They're very proud of who they are and they always make sure that any time they're filling out forms and they try to choose what race and ethnicity, if it's not there, they'll write it in. That's just what they do. They write it in.

EmbraceRace: That's great. You know, we've asked you questions that really get at your own experience, your children's experience, and so on. Part of the reason too that we asked both of you is that we know that you have a lot of experience with other adults and families and educators, in both your cases and parents in both your cases too for that matter.

If you are a caregiver to one or more young children of color, what's the biggest single challenge you've faced in trying to raise that child or those children to be resilient and joyful?

What are the two or three challenges that you think about when thinking about young kids of color and raising young kids of color to be joyful, resilient, to recognize the full humanity of other kids of color and of all kids? What are the two or three challenges that you feel like parents of young children need to meet to raise those kids?

Dolores Sosa Green: Yeah. That is a hard question. I think one of the challenges is more within the family, the family not being comfortable speaking about race but also even educating family members, especially when you blend two different cultures together and ethnicities and races, being careful not to label the children certain nicknames because what that does is it kind of exacerbates the issue of them feeling like they're less than other races.

For example, I'll take myself as an example. I've heard it in the work that I've done in the past with when I was working with K through 12 grade students is that, "Well, my sister is a lighter skin color so she's called guera meaning White, "And I'm called morenita, you know, darker skin. That morenita nickname was always taken in in a negative light. It's unfortunate because that's what we've come to. Just being careful and educating ourselves within the family and other family members of the words we choose and what nicknames we assign to our children, especially who are of different races.

I know growing up, I didn't want to go out and be in the sun and get darker because even in my Mexican culture, those who are lighter skinned are so-called “better” versus those of us who have much more color. That's a challenge just within the family, educating the family. Externally, obviously, we can't control what other people say so you have to prepare your children as to how to handle that. In the case of Maya, she knew how to defend herself. A child that doesn't really talk but spoke up that day because it offended her so deeply to voice that and that it's okay to voice that and be brave enough to do it and to also teach our children to speak up for others who are maybe experiencing the same thing. I think that's also very important.

For me, internally and external challenges exist in that respect. Of course, we really can't control the internal either, especially with some family members, right? You just teach your children how to speak up for themselves and not to be afraid to do it.

EmbraceRace: That's so interesting. We had a really interesting webinar conversation about colorism some months back. Lori Tharps had written a book and interviewed lots of different families across racial lines about colorism and what you said about it's in the family it's so relative, right? Where people would say, "I was the dark one" and she'd say like, "Wait, what?" You know? It really is about who is sitting next to you at home and those comparisons can really do damage for a long time. Yeah. It's really fascinating.

I just wanted to share some of the amazing responses, incredibly thoughtful responses folks are sharing. There are several responses about teaching children, I assume these are children of color, to be upstanders, right? You mentioned that, on behalf of others. Colorism gets several responses as well. Here's one man, probably a dad, who says, "I hate that I choke up on talking about race with my kids. I'm a Hispanic dad of mixed race, Black/White kids.” Again, more colorism. Lack of diversity. There's several references to the political climate that makes it so difficult for BIPOC children right now. The hard stories about race and why things are difficult for people of color historically and in the present. Lots and lots of challenges.

Someone speaking about the expression … mejorando la raza or adelante la raza about marrying light, doing that for your family. Just a lot of stuff that's really deep. Also, a number of responses from adults with children where there's no one who looks like the children in their immediate environment. Perhaps even within their own families. That's a real challenge. Brigitte, what can you share?

Brigitte Vittrup: Well, I think part of the challenge, and it's been both for my own family and what I've heard from other families that I've spoken to, is just having these positive role models that look like the kids. Like I mentioned with my daughter and her hair, finding positive role models that really embrace their natural hair.

It was so lucky, fortuitous, when she was three. I was going to the UPS store, I passed this woman in the parking lot, and she just said, “Hi,” and you're being nice and you say hi because you pass somebody. Then she turned around and she said, "If you need a place for your daughter to have her hair done.” She gave me her card. It ended up being just the best thing ever. She was doing hair out of her own house at the time, specializing in natural hair. Now she's practically growing an empire. She has a salon in Dallas called Her Grown Hands. Her name is Whitney Edie and she's phenomenal. Now she has the salon. Taking my daughter there where she is there with all these other Black women and children with natural hair, she feels so special when she's in there because here are all these people that have hair like her.

I realized how important that is, just being able to have these opportunities. For some families, if they live in a neighborhood that's not very diverse and if they're in the minority in that particular neighborhood, it can be hard to give your children those role models, those examples and so trying to find them in books, in videos, in the media because I think it's so important to be able to give them that. Then at the same time, I also think it's important to give them examples and teach them about other people's background and heritage and experiences and really having those very direct intentional conversations about race, about race-related issues, about our own experiences and about other people's experiences.

Obviously, for me, as a White woman, my life, just as a function of me being White, has been privileged. For my husband, not so much. He's had very different experiences. I think for everybody it's important that we teach our children that some of these kids they go to school with have very different experiences and it's important to learn about all of it and to really have these conversations early on, not just with the teenagers.

The kids understand the concept of fairness very early on. I mean, even my daughter when she was seven and she heard about everything going on with George Floyd because it was all over the news. You can't avoid it. You can't pretend it's not happening. They're hearing it and so if you don't talk to them about it, as uncomfortable as it might be for parents and sad that children are having to learn about this reality, they're hearing about it and we need to interpret those messages for them. Next thing you know, my daughter and her little friends, they're on Kids Messenger and they have a fist like Black Lives Matter, like that's their little profile picture, they all chose one, her and her little White friends. She would talk about it, about how this is not fair, and you shouldn't treat people like that. I just think it's really important to have those conversations regardless of how uncomfortable it might be at times.

EmbraceRace: And because, like you say, they will encounter this stuff, right? When you're prepared it doesn't crush you quite as much. That beautiful example of your daughter and her friends just knowing that some people are going to not like you because they have these ideas about the color of your skin but then you have these friends who think that's really dumb and they're right. It's not like painting everyone with the same brush but preparing them for, "We don't believe that. We don't believe there's a racial hierarchy. We believe everyone is valuable. Poor them, they believe that."

You talked about learning about others, learning about other people, other cultures, etc. Specific resources. There are some wonderful books, Matthew Cherry's Hair Love, which also is a short film.

Can you give us some specific ideas about what you would need, what we EmbraceRace might possibly do to support you in this work? What does that look like? What's some language? What are some questions? How do you respond to the sorts of things that kids are liable to say? What specific things could we possibly offer that would be of tangible support to you in this work?

Dolores Sosa Green: Sure. You know, because I do work with children, we have early childhood education where I work, things, books, that really embrace the different cultures and embrace the kids that look like them, so great stories. I think we've improved a little bit in that but there's still a lot more room because when you read books it's always about a White character. It's never about a different ethnicity or race. Just more variety in that sense. Also, just making sure we have activities that we can do with our children at home or in the classroom that really bring out the being proud of who you are and the skin that you're in, being proud of your hair, going back to that, and just embracing it.

Even in communities that are of color, predominantly of color, who have maybe experienced a lot of poverty, and already feel pretty much less than because of where they are living and who they are, and those community centers that are around them and providing activities and discussions about race, I don't think in the 13 years that I worked at my previous organization in after-school programming, we didn't speak a lot about race. We did talk about that regardless of where they came from and being predominantly Hispanic students, regardless of that, they could achieve great things academically, that just because where they came from, didn't mean that they weren't just as smart as White students. Because that's the message that they got.

That's where I pretty much was focused on that end of it, but I never thought to include the discussions to go with that. I think that's incredibly important to do that within communities of color because I've always said that ... I had one student of mine who said it one time, “I'm tired of being that it's miraculous that we're the first to do this, the first to do that.” I would like it to be something common, that it's already expected of us, not that we're the first. The first is great but not when because you're Black or Brown, that, "Oh, it's a miracle that you made it!" You know what I mean? They want to feel that they can accomplish just as much regardless of who they are.

Making sure we have activities that we can do with our children at home or in the classroom that really bring out the being proud of who you are and the skin that you're in, being proud of your hair, going back to that, and just embracing it. Even in communities that are of color, predominantly of color, who have maybe experienced a lot of poverty, and already feel pretty much less than.

Dolores Sosa Green, Director, Transforming Lives

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Dolores. Brigitte, what's your thinking?

Brigitte Vittrup: What I'm finding is a lot of the workshops that I've done, what parents will say, is that they just really need very specific, very clear guidelines. Like, "Okay, I know that I should be talking about this. What do I say? How do I say it? How do I begin these conversations?" I think that there is a lot of resources out there and there is a few books but they don't get into the details. For somebody who is not used to having these tough conversations, and especially these days, when I have parents saying, "How do you separate race and politics? How do I talk about these things without mixing politics into it and with everything that's going on in this world right now?"

They just want very clear guidelines for specific scenarios. People have so many different experiences and even how to start, where to go, what to do. And then one thing that I'm noticing also is in a lot of these webinars that you do at EmbraceRace, following the chat whenever that's available, people will start commenting on each other's posts and they'll have these little conversations, these little side conversations because I think people really need a forum to have these conversations where they can meet others that are in the same situation.

You know, for interracial couples that are raising kids, that's one challenge which is very different from somebody who is a single mom raising a kid of a different race and it's different from somebody who is Asian and immigrated here versus somebody that was Asian but it was their grandparents [who immigrated here]. All of these different scenarios, I think when there are community groups where people can not only find others that are in their same situation but also share across racial groups and across experiences because I think that's sort of what we're lacking a lot just in this country as a whole. It's those conversations across racial barriers and really teaching our children, providing our children to have those conversations too because, again, kids will talk about it but adults tend to be, "We'll talk about it in our own little group" but we're not comfortable talking to others and reaching out and that's really what we need to do in order to understand each other's experiences.

EmbraceRace, Andrew: Brigitte, we've talked about this a fair bit but, certainly, the community building piece and the relationship building in addition to the resource piece is something we explicitly want to do and some of it is about sharing experiences with folks who are similarly situated. We’re finding, increasingly, that adults have our own things to deal with. We have our own experiences. We have our own entanglements and tensions around race. Engaging our kids in ways that we find healthy around race becomes a lot easier if we're able to work through some of our own things. Sometimes that's done much better, more effectively, in community with others, who are like and sometimes unlike ourselves.

We’re finding, increasingly, that adults have our own things to deal with. We have our own experiences. We have our own entanglements and tensions around race. Engaging our kids in ways that we find healthy around race becomes a lot easier if we're able to work through some of our own things.

Andrew Grant-Thomas, EmbraceRace

EmbraceRace, Melissa: Dolores, you were saying also, that people want not only the book but they want the guide with it. Because they want to know how to have the conversation. It's funny. We get that a lot and we're creating this video we keep talking about but it'll be out next year, Reading Race in Picture Books where we show different people having the conversations in classrooms with parents. I guarantee after people see that, those seven examples, eight examples, the question will be, "Yeah, but what about my kid who X, Y, Z, who this, who that?" because it is so specific to the kids, right? All we can really do is give guidelines and really push people to jump into the conversation, to ask the questions, to be the expert in their kid.

Dolores Sosa Green: Yeah. It almost feels like for our early childhood education, for our parents, we have something that's called Parent Cafes. It would almost seem appropriate for something like that to have that discussion because we can get parents who are experiencing this to be a part of that. I mean, I think it would just change a lot of things and make it a lot easier on the parent to hear from others that are going through the same things. We all feel alone sometimes. We don't know what other parents are going through that are like us. Because we're so busy we don't talk to others as much but if you get us in a group, like I said, on our Parent Cafes, we have at the Center For Transforming Lives, I mean, that would be great. I'm going to have to talk my boss into that. Something like that.

EmbraceRace: We just saw an idea borne right there. We have someone asking a question that's really two questions spanning both the parent/guardian role and the teacher role. This person is both.

The first question is, "My kid is dark Brown, BIPOC (Brown, Indigenous, People of Color) kid, living in a predominantly White community. Her experience is different than my own, growing up in a Brown community. How does the support we provide BIPOC kids differ depending on their surroundings?"

The second question is, "As a preschool teacher, how do I support the few BIPOC kids I have in the mostly White classroom?"

Brigitte Vittrup: Well, it's interesting. I like the question about the early childhood classroom because I've talked to a lot of teachers that are struggling with that too. I think part of what we have to do is to make sure that we're not presenting things as this tourist curriculum. You know, "It's January. Let's learn about Martin Luther King and in November we learn about the American Indians." That it has to be so common that we talk about people's experiences and people's lives and show them books and pictures, even if you have an all-White classroom, to have pictures that represent other kids as well so that it just becomes a normal part of their environment. It's not something that's, "Ooh, we got to celebrate Black heritage now." That we really do it year long.

Because that way those kids, if there only are a few, if it becomes part of the regular curriculum, they will feel like they are part of this, they belong here, even if they might be in the minority. I think it's so important because race becomes a lot more salient to kids as well when they are in a group or they're in the minority. You know, it's very different if you're in a group where you're like most other people. I think definitely having those frequent conversations and whether you're using books as springboards or looking into traditional or Indigenous or things that are specific to a cultural heritage, some of these toys and resources and making them not just a one-time thing but part of just the regular curriculum.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. It would be really great if people have November vacation or break to dive into, as a family, understanding and starting a tradition of having an ongoing conversation and learning and unlearning experience around Native American culture or various cultures and First Nations, learning more about that instead of what we do, which is November is we're going to celebrate all things Native American when it's really all year.

EmbraceRace: Dolores, did you want to offer some thoughts on that one?

Dolores Sosa Green: I think Brigitte covered it pretty well. One thing I would like to see in the early childhood, though, is making sure the toys that we buy, the dolls, making sure that we have a diverse selection of dolls of all different ethnicities. One of the things that a good friend of mine had told me a long time ago, because they served predominantly Black children, that it was so hard to find Black dolls. That's what she would ask donors to donate or, "Can you please donate Black dolls?"

It's gotten better. We've got different Barbies now but there's still a lot of room for improvement. Making sure we make that a part [of play] when our children are younger, for the girls. For the boys, the same thing. You know, the boy dolls. Making it multiracial, different ethnicities, those are great. Black firemen, whatever that may be. That would be great because then they could see themselves in those roles. They see that they're included and not excluded.

EmbraceRace: How do we nurture BIPOC children to be resilient while not making themselves self-conscious about their race or difference? That's a fear I think a lot of parents have.

Brigitte Vittrup: I think a lot of it has to do with how often you talk about it and how much it becomes a normal part of celebrating who you are at home and with the resources that you surround the children with. To not make it something that, "Now we're going to sit down and have this difficult conversation,” but where it becomes just part of everyday conversation and everyday things that you share and things that you read about. I think that's really important so that it doesn't become something like, "Here's something special and I'm very different and now I'm really noticing how different I am." Again, like some of those questions in the beginning about really nurturing their self-esteem and a positive racial and ethnic identity.

Dolores Sosa Green: Yeah. I agree with that. Just regular conversations because eventually they get to the point where they're comfortable and they start coming to you and saying, "Hey, what do you think about this?" It's just a natural thing that comes about. I love that both my daughters do that now. They're comfortable. I mean, they're pretty confident kids. Yeah. Everything that Brigitte said.

EmbraceRace: We have a number of questions from parents of multiracial children, probably multiracial biological children where, essentially their dad, in these cases, doesn't want to get involved. Perhaps it's a single mom in some cases or it may be the couple is together but the dad doesn't want to engage nearly as much as mom does in the question of racial identity. You have a multiracial child who doesn't get the connection with his/her/their father and mom is wondering what do I do?

There's one woman, in particular, who is saying, "How do I speak to my child about the fact that he has an Asian American heritage with a father who, himself, the Asian American, doesn't want to engage the child in this issue?" How does this mom represent that part of her child’s identity to which mom can't claim for herself?

Dolores Sosa Green: Yeah. That's a tough one. I have experienced it in my own household. My husband doesn't talk much about his race. He doesn't want to make matters worse. I don't know if I'm explaining it correctly. He doesn't want that to be the focus. He wants it to be where, “You are who you are. You're a good person. Do what you need to do. You need to work hard.” You know, I don't know the reason for that. I, myself, have experienced that challenge because I've been the one primarily who brings it up. It may be because my girls are girls and they come to mom, right? It could be that. I don't know if we had a son if it would be any different.

I know that even my beautiful mother-in-law who passed away earlier this year, we had those conversations. I wish I could answer that for you because I don't know. I just know that, for me, it was important because I was seeing some of the signs early on with my children as to their feeling uncomfortable with who they were at the time and I just needed to intervene at that point. Maybe part of it was my fault too because the story I told you about my oldest daughter when she came to me and said she didn't want her dad to pick her up. I never told him about it because I didn't want him to be hurt by it. In a sense, I was trying to protect his feelings but I took it really hard when she came to me about that. It is a two-way street but if at least one of you does it, I think it's better than nothing. I wish I had a better answer but I don't because that's a hard one.

EmbraceRace: That's really real about how hard it is. Thank you for the honest answer. And condolences on your mother-in-law on her passing. Brigitte, any thoughts about that?

Brigitte Vittrup: I mean, it's hard in any situation if you have one of the parents not as involved. That's with this as with everything else. I do think that it's important if you can have the conversations with the other person and I think especially if it's a dad that's not as involved and if you have sons because that is such a powerful role model in their life. But it's not to say that the parents are the only role models. There are others. There are teachers and other family members, close friends, that can serve as those role models. I mean, you have single mothers raising sons that grow up and have a strong gender identity and feel good about themselves because they've had other role models, even if it wasn't in the home. If you are very involved in having these conversations and the kids get used to having these conversations then when the other parent is around, maybe you can pull them into some of those conversations just because it just becomes part of what's going on in the family. It's always hard. We can control ourselves. It's hard to control what other people are doing.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. Thank you so much, Brigitte and thanks, again, Dolores. We're just about at time. I want to remind you that again, like most of our webinars, this really is fact-finding, insight-finding, trying to guide our effort to be as attentive as we can to the needs of the parents, the educators, all the adults in the lives of young children, right? Zero through eight and young Black, Indigenous children and children of color, in particular. As part of this effort, this was one webinar. Our focus here was on parents and caregivers. We're going to have another webinar on Thursday, which will be especially attentive to educators and the roles that educators can play in this work and how, again, EmbraceRace can support educators in doing this work.

You don't need to be an educator to come, although, educators are certainly especially welcome. Please come back if you haven't registered already for Thursday. Also, as part of the fact-finding, we'll be sending out a short survey to those of you who registered and we would really appreciate it if you would take a moment, it'll probably take about 15 minutes, to answer that survey. We'll send it out probably tomorrow with the recording here. We'll include, as soon as we can, a list of the resources and others that we think will be helpful to you. Please do look out for that survey, take it if you can, look out for Thursday's webinar.

Thank you for sharing so much. We always learn so much, not only from the guests but from those of you who participate. You guys make us better. Thank you, Dolores and Brigitte, thank you. Thank you for all who attended. Really appreciate it. Take care, folks. Bye.

Special guests

Dolores Sosa Green

Brigitte Vittrup

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe