"Fairies Are For White Girls" And Other Lies My Sister Told Me

A Talking Race & Kids conversation about the importance of inclusive fantasy fiction for all kids with kidlit authors Marti Dumas & Zetta Elliott

Watch the conversation Andrew and Melissa of EmbraceRace have with Marti Dumas and Zetta Elliott, two fantastic children’s book authors, about how inclusive fantasy fiction empowers all young readers. They argue that magic is ultimately about power, that ALL children need to know that they can make--and unmake--worlds, both real and imagined. Marti and Zetta also read from their books, suggest inclusive fantasy fiction titles for the kids in your life, and take EmbraceRace community questions. Watch the video or read on for a lightly edited transcript.

EmbraceRace (Melissa): So, we're here to talk about inclusive fantasy fiction for kids. A lot of us - as parents, as folks in the literature domain, writing it, reading it - are really desperate to find more fantasy and Sci-Fi works for children that feature protagonists and heroes of color. Especially families of color, families raising kids of color, are searching and we're just not finding very much.

We're starting to find more and more of it, but not enough, and what's so mind blowing to me, is that it seems that the genre fantasy fiction can be so radical. It's propelled by oftentimes upending convention. But still, it remains super white, and often super other things - super straight, neurotypical ... well maybe having superpowers is not neurotypical …

Today we're going to talk today to two authors who think about this a lot, and who are writing some of that, some of those books, some of those stories that we all need to be able to see ourselves as folks of color, or even as white folks seeing folks of color, creating our own worlds, and having visions that we can aspire to and move towards. So, we're really excited to be having this conversation!

EmbraceRace (Andrew): Yes, I'm looking forward to hearing your take on … the extent to which you see the imaginations of even writers in fantasy fiction being limited, and what that means for the rest of us, for the reading public.

Let me offer quick introductions. The short story is that they're fabulous, they're awesome, you need to read all their work.

Author Marti Dumas

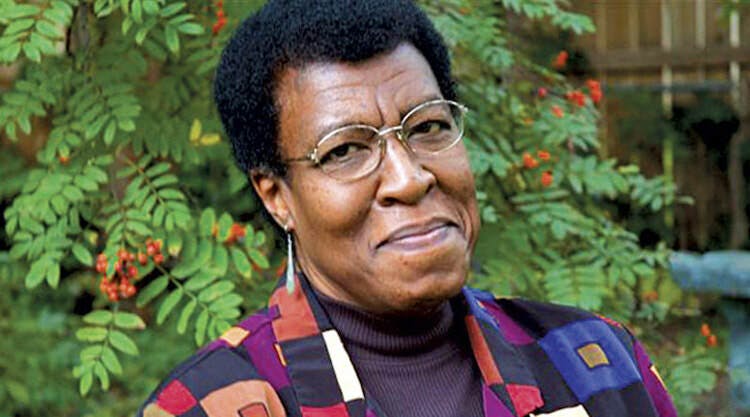

EmbraceRace: Marti Dumas is a mom, teacher, writer and creative entrepreneur from New Orleans. We did confirm that she is in New Orleans right now.

Marti Dumas: At this moment.

EmbraceRace: At this very moment. An expert in childhood literacy. Marti has worked with children and teachers across the country for the last 15 years, to promote an early love of reading books in and out of the classroom. Her best selling Jaden Toussaint, The Greatest Series, combines literacy with STEM skills, and humor, and adds much needed diversity to the children's chapter book landscape. Her latest books, Jupiter, Storm and The Little Human, are middle grade fantasies being heralded for their skillful combination of science, family and magic. Welcome Marti.

Marti Dumas: Thank you so much.

EmbraceRace: Jaden Toussaint, The Greatest. Big Afro even bigger brain.

Marti Dumas: Giant Afro, even bigger brain.

Zetta Elliott: I love it.

Author Zetta Elliott

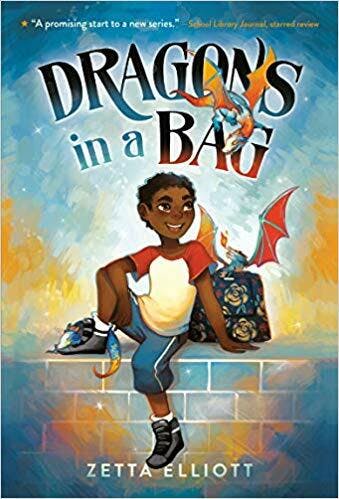

EmbraceRace: Zetta Elliot is an author, poet and playwright. She's the author of over 30 books for young readers including the award winning picture books Bird and Melena's Jubilee. Her urban fantasy novel Ship of Souls was named a Book list Top 10 Sci-Fi Fantasy Title for Youth, and her wide time travel novel, the Door At The Crossroads, was a finalist in the Speculative Fiction Category of the 2017 Cybils Award. Dragons in a Bag, a middle grade fantasy novel was published by Random House in 2018, and named an American Library Association Notable Children's Book, and the sequel, The Dragon Thief, was published … today!

Zetta Elliott: Thank you.

EmbraceRace: I have to add that Zetta is an advocate, a fierce and insightful advocate I must add, for greater diversity and equity in children's literature. We're absolutely delighted to have you both here.

Zetta Elliott: Thank you so much.

Marti Dumas: Thank you.

EmbraceRace: So, we always like to get some definitions of key terms. In this case, I'll start up with you Marti, could you give us, like just going over the difference between speculative fiction, science fiction and fantasy?

Marti Dumas: Okay. I was going to say, I will give you mine, but I will tell you that people will disagree. So, Zetta should jump in with hers, her tweaks, or her changes there.

Zetta Elliott: I'm glad you're going first.

Octavia Butler, speculative fiction writer extraordinaire, once said: "I began writing about power because I had so little."

Marti Dumas: So, speculative fiction is in the, I want to say it's in the crossroads between possible, and also in the fantasy in that, time doesn't always factor into speculative fiction in the way that we're thinking of it, like in a linear way. So then, it is very much about what could be, what might have been, how we might be able to change the future because of the past or vice versa. So, if you were thinking about the things that people really have always thought of as speculative fiction, then we have to give a nod to Octavia Butler, and we can go forward from there, so things in that category.

Fantasy is going to be things that have some touch of magic. So, there are things that are made up. There are fantastical books, for example my Jaden Toussaint books have a cat and a guinea pig that give side commentary throughout the story. So, obviously that's not real but I mean, it could be, because they don't speak technically, but they are definitely communicating with each other and they have humorous things to share with us. But, it doesn't actually knock out those stories out of the category of realistic fiction. So, they are chapter books, but there's a little fun in there, but it's not enough to be able to take it out of that. Then, what was your last one? Was it science fiction?

EmbraceRace: Science fiction, yeah.

Marti Dumas: Science fiction, that is also in the possible, but it starts with some root in science. Usually hard science, but depending on which branch of science fiction you're looking at, there are branches of science fiction that take science fact, and build on fact with only documentably possible things. So then, that's going to be your hard science fiction. Then, there's science fiction that pushes a little more into the fantasy realm because, it starts with an idea of science, maybe a spaceship, but then, it doesn't continue to build on the science. It just maybe does a little hand waving, maybe a little magicking. Some people will argue with me, I'll just put this one out there because like Star Wars, in my book, is really fantasy and not at all science fiction, but you would not find it categorized that way in bookstores. But then, that's why we get to have conversations and decide. So Zetta, where do you disagree?

Zetta Elliott: I absolutely agree with what you said about science fiction. I generally think of myself as not writing science fiction, because I don't anchor the narrative in hard science, and the people that do take that very seriously. I tend to say that I write speculative fiction, because speculative fiction for me is an umbrella term. Within that, you have science fiction, fantasy, paranormal, horror, alternate history, time travel. You have all of these different genres. For quite a few of us, we mix. We have overlapping ideas. So, it's useful to know the conventions of each genre, but I find that I really only pay attention when I'm transgressing those conventions. So, I never thought about it when I was a child reading fantasy. I don't remember reading science fiction until high school, and then it was Isaac Asimov, and I absolutely hated the book that we read. So, I think after that I was like, "I'm never reading that again." But loved The Mists of Avalon.

So, anything that was a little bit historical, and then added some kind of magical elements, and that tends to be what I write. I write historical fantasy. I'm also taking historical parameters, and then speculating, which is often what you have to do if you're writing about Black folks because, the historical record is incomplete especially if you're writing about black women, especially if you're writing about poor Black people, especially if you're writing about disabled poor Black people. So, speculative fiction for me is useful because it lets you pick and choose. Then, when people are struggling to put you in a box, they have this big umbrella and all of us, so many of us, more of us can stand under that.

EmbraceRace: Great, that's helpful. People will take you down afterwards maybe.

Marti Dumas: They'll definitely, yeah.

EmbraceRace: So, I'm wondering, Zetta, we got the title [for this conversation] Fairies Are For White Girls, and Other Lies My Sister Told Me, because your sister actually told you that, right?

Zetta Elliott: Said that to me, yes.

EmbraceRace: So, I'm wondering how with each of you, how you got into writing fantasy, and how you came to love it. I will come out as someone who I guess maybe if it's loosely defined, likes some fantasy, but just always thought that was for other people. I'd love to hear how you guys started orienting yourselves towards fantasy fiction and when. Have you always liked it?

Marti Dumas: I can jump in, but do you want to go first Zetta? This is an amazing episode title, so I'm super curious about it.

Zetta Elliott: Well, I did a couple of school visits today, and I was telling the kids how when I was young, I loved fairies, and elves, and unicorns. Then, one day my sister came into my room when I was drawing some fairies and unicorns, and she snatched my sketchbook away from me and looked at it, and was just disgusted.

I really didn't encounter much bullying in my childhood except from my big sister. We were attending predominantly white schools, and so in some ways, she was almost the only Black role model I had, who was close to me in age. She was into Prince and she wore stilettos to school every day, so I was definitely not as cool with that. I was used to her teasing me for being a geek, but then she saw the fairies and was like, "Oh my God! What's wrong with you? Fairies are for white girls." Of course, that was the worst thing you could say to a young Black girl, who is trying to feel secure in her identity as a young Black girl. It made me feel completely inauthentic and a fraud.

There was no community. I didn't even know that many Black kids, because there weren't that many at my school. But, to suddenly be told that there was something wrong with me, and that liking unicorns and fairies was something I should be ashamed of... So, for maybe 10 years, I didn't talk about it, and I didn't really tell people that that was what I liked.

Then I went to college, and my roommate walked in on me while I was drawing some fairies, and did not make fun of me. So, I had that moment where your heart ceases, and you're like "Here we go again." She was a blonde haired, blue eyed girl of German decent, and she was like, "I have a book of fairies, do you want it?" She went and got a book of fairies for me, and then she went to the Met in New York City and brought me a picture of the unicorn tapestries from the cloisters. And just was feeding my imagination, and I just thought, "I've been doing it on the sly, I've been doing it on the down low to keep it quiet, but I don't have to do that."

Then, a couple of years later, actually the very next year, I went to England for the first time. My whole life, I had been oriented towards England because I had been reading British fantasy fictions from the time I was very young. The first day we were there, they took us to Arundel Castle. We're in this amazing big castle, which has this gorgeous courtyard, and there was a stage in the courtyard. In Canada, we went to see Shakespeare plays every year at Stratford, in Stratford Ontario. Every year, I had gone to see those plays and I had never once seen a Black actor on stage. Here I was in this castle in England, and they were doing The Tempest, and yes, Caliban was a Black man, and so was the prince. What's his name? Ferdinand or whatever?

He was so good looking, and one of the princess' ladies in waiting was... That was so mind blowing to me. So, that was when I started to make the connection that, I didn't have to be ashamed about liking fantasy, that there were Black people in history, and even if there weren't, you could still cast them in those historical roles, and in those historical spaces. I think that really changed something for me.

By the time I was in my 20s, if someone had said to me, "Do you like fantasy?" I would have been like, "No. I don't read that kind of stuff. I read historical fiction, and I'm writing my dissertation on lynching. That's what I'm about." Then I work with kids, and when I would talk to them, I just started thinking about the books I'd read and almost everything I read as a child is fantasy. It was The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, E. Nesbit and even The Secret Garden felt like a fantasy to me. So, a lot of what I was reading, feeding my mind with, and doing my thesis in high school on The Mists of Avalon, I just... I don't know if I tried to shut that out of my mind because I still was balancing that shame aspect of what if I really just thought I'm someone who's invested in history and I don't do that freaky spaceship stuff. Truth is, I do.

Marti Dumas: Well, I wish that we had been able to be friends.

Zetta Elliott: I know, right?

Marti Dumas: Yeah. When I was in fourth grade, we had to do a project on mammals, and I convinced my fourth grade teacher to allow me to do my mammal project on unicorns, legit. She said, "If you can find sources that are not fantasies." I did.

EmbraceRace: Go Marti.

Marti Dumas: But, I also have always had a love... I think that there's the feeling of wonder, and the feeling of the possible is a thing that speaks to some people. It definitely spoke to me. So then, I also resonate with the idea of The Secret Garden feeling like a fantasy because, the whole book is just a moment of wonder. There's very little plot in the story. It's just like a giant moment of wonder. Who doesn't want to have that? It's like what the movies were in the 1920s. You want to have a little bit of, "Wow! This is possible. The world could be this beautiful and my life could be this beautiful." So, then that's where the fantasy comes in. I mean, there's also a power element to it too, particularly that I think spoke to me as a child, and I know speaks to the children that I know who also enjoy that kind of thing.

Zetta Elliott: I should say, just on behalf of my sister, we're still not that close, but I have to say that I was not watching Game of Thrones until she came to visit me in New York and was like, "Oh my God! I can't believe you're not watching it. It has dragons you know." Then I was like, "What? It has dragons?" That was the first time where she acknowledged that I like fantasy, and that there was nothing wrong with it. That actually, the rest of the world loves fantasy too. So, then I subscribed to HBO just to see Game of Thrones, and those dragons were great. Their mother was problematic, but yeah.

EmbraceRace: It seems like your sister has some of the same effective tools now she had then. But, that's a different conversation.

Zetta Elliott: Yeah, we don't have time for that kind of therapy.

Find more at martidumas.com

EmbraceRace: All right, all right. I did want to followup on that question though about the writing for both of you. Clearly, you were readers, and that was phenomenal for you. Marti spoke about the sense of just wonder, maybe that's enough. I can totally relate to that. I wonder though if in retrospect, as you look back, was there even more than that going on for you, for both of you? But especially, say something about the writing. How you write. That's obviously not an easy path.

Marti Dumas: So many things in my life have happened because of children. I was a classroom teacher. I taught elementary school for 13 years. The first stories, the first novel length stories that I wrote, I wrote for the children in my classroom because, there were things that were missing that they needed. So then, I wrote the stories for them, and they used them, they consumed them. We had to reprint them and stuff like that, that was fun.

But then, the first story of mine that was published, I actually wrote for my daughter, who is now 14. When she was six, she was an amazing reader. She still is an amazing reader, but she was an amazing reader, but six. The kinds of stories that she wanted to read were not appropriate for her for many reasons. One, because as a six year old, she was an extremely fluid reader. So, she would read through books without needing to ask questions. So, you maybe wouldn't have noticed that she had finished a book, so that you wouldn't notice to have the conversation with her to say, "What did you think about this? Did you notice this part? Did you notice the way that they had this character do this?" So that you could balance out the imbalances that were in the stories.

So, I was like, "Well, I'm going to write her one. I'm going to put her in it." So then, my story Jala and The Wolves, literally the character is my daughter as she was at six. Not a representation, not some core character traits, actually her when she was six. It was amazing to me that anyone else besides her wanted to read that story. Luckily, other people wanted to read the story. She was very much into that feeling of wonder. The idea of being able to be in charge, and in charge of herself, and in charge of her surroundings. So then, what better way to be able to do that for her than in a story?

So then, I think that being able to think about children really specifically and what they need, has really driven me to write fantasy, which I know doesn't sound exciting. But children need fantasy, they need to be able to stretch their imagination. They need to be able to imagine the world being different than it is, even in order to understand the world as it is. If there's nothing to contrast it with, then you can't really see what's there in the first place. That was maybe too far in, but I really think that and have experienced that with kids. Where, they think of something that is impossible, and it really helps them to understand the possible.

More at zettaelliott.com

EmbraceRace: That's lovely. Zetta, did you want to answer that question about how you got to writing?

Zetta Elliott: Sure. I've worked with kids for 30 years. I'm not a certified teacher, but I worked with kids in after school programs. I had one girl whose mother was in prison, and she was acting out at school. She would come into the after school program and punch people. When I found out that kids were teasing her and calling her jailbird, I was like, "You know what? Lots of people have a family member who's incarcerated. My brother was in jail for a while. I'm going to find you a book that's a mirror." I couldn't find a single book about a little Black girls whose mother was incarcerated. So, I wrote her a book.

I think it helped that I was doing this dissertation on lynching, and I was focusing on trauma. I think it's Elaine Scarry who said, "Trauma resists representation." So, if you're dealing with kids who have experienced trauma, they're having a hard time articulating it. It's difficult to represent in narrative form, in visual form. There are all these challenges. So, I wrote that story for her, An Angel For Mariqua, which is realistic fiction. Then, I think the next thing I wrote was called Room In My Heart, which is about two little girls dealing with their father having a new girlfriend after their parents got divorced, which is exactly what I was going through in 1981 when I was 8 years old. I remember showing it to my father, and he threw it down on the floor, he wouldn't even finish reading it.

So, I think as an adult, I was trying to in some ways use fiction to heal, use narratives to heal in a way. So, I wrote those two realistic stories, and then I almost immediately went and started writing a book about a phoenix. Then, I had all these other magical stories. I realized they were a response to, and a way to talk back to the books I had read as a child. So that, once you've gone to graduate school, basically everything you loved as a child has been destroyed because then, you start looking at it critically where you've got your Black feminist lens. So, The Secret Garden is sexist, and racist, and imperialist, and elitist, it's a disaster, and I still love it, and I still give it to my niece for her birthday. We can talk about it. But, it was a way of acknowledging that those narratives made an impression on my imagination.

So, I wrote that essay Decolonizing The Imagination, and what it was going to take to de-center whiteness and Britishness specifically, and put something else in its place. That was really hard to do because I didn't have an understanding of African mythology, I didn't necessarily have a lot of understanding of Caribbean mythology. My father's Caribbean. So, then it meant doing a lot of research. I found that, when I was writing fantasy fiction for kids, I was ostensibly trying to heal them, but also trying to heal some of the things in myself that were missing or that were ruptured that needed expression. Being able to say, "I can't go back and draw on my African heritage because guess what? The Transatlantic slave trade. Let me write about the Transatlantic slave trade." Then, you end up with the mermaid story, Mother of the Sea, which I say is about a mermaid who destroys a slave ship, but it's also a way to start dealing with African religion, Yoruba specifically.

More at zettaelliott.com

It's difficult because I think of myself as a realist, and so, I always want to have realistic representation in my stories. I think even though I say magic is about power, and all kids should have a chance to see how they would wield power, quite often when you've been vulnerable, or marginalized, or oppressed by people with power, you don't know how to use power responsibly. It's something you have to learn.

So, that's been I think a big part of writing fantasy for me is, not just magic wand you can do whatever you want to do. There's more of a complicated psychological process to it, and a sense of responsibility and risk. I know I often hear from editors, "Oh, but it's too sad," and then I came up with Dragons in a Bag, but I like what Ramón Saldívar had to say, which is that, "Fantasy isn't a way for many people of color to escape from reality, but a way to engage with it more deeply, and a way to find justice within a past that has not been just for many of us."

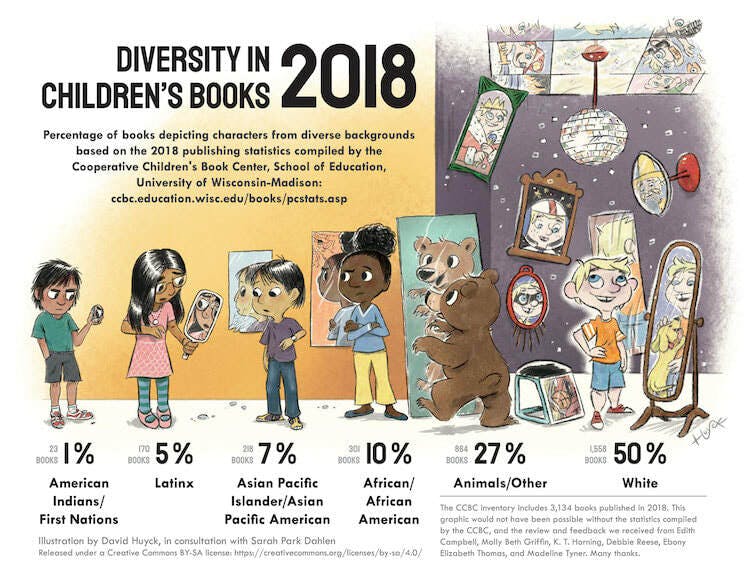

EmbraceRace: Thanks for that, Zetta. I want to talk a little bit about numbers and what we're talking about when we say there's a real lack of representation of characters of color in children's literature, but also in children’s fantasy fiction. So Zetta, do you want to talk about these slides?

Huyck, David, Sarah Park Dahlen, Molly Beth Griffin. (2016 September 14). Diversity in Children’s Books 2015 infographic. sarahpark.com blog. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2016/09/14/picture-this-reflecting-diversity-in-childrens-book-publishing/ Statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp Released for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Zetta Elliott: I'm sure a lot of people have seen these graphics circulating on social media. Sarah Park Dahlen, at St. Kate's University in Minnesota, commissioned them, and the illustrator is David Hayek. But, they're building on Rudine Sims Bishop's metaphor of books being windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors. We see the white child on the far right hand side, hand on hip, he's feeling confident, he's feeling good about himself, and he's in a room full of mirrors. In every mirror, he sees himself as the hero. He's the astronaut, the king, the firefighter, the scuba diver, the basketball player, because so many books, 73% of them reflect him, center him, and he gets to see himself in every heroic role.

Zetta Elliott: Then, we see the kids of color and the Indigenous child don't have that same opportunity. When they look at themselves in the mirror, they look miserable. We do find that a lot of times in the publishing industry, when they're writing books about kids of color, and Indigenous children, when those books are published, they're problem narratives. There's a problem, something bad's going on that the child has to overcome. So, those children don't get the same opportunity to feel empowered, or excited or have a laugh about a mystery, or an adventure narrative, or a ghost story, or all those kinds of things, which is incredibly unfair. Of course, we have 12% of the books about animals and trucks.

Huyck, David and Sarah Park Dahlen. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/.

Zetta Elliott: Then, by the time we get to the updated graphic in 2018, we see that the publishing industry has not increased the number of books about kids of color and Indigenous children, they have simply doubled the number of books about animals and trucks. So, they have reduced the number of books about white children from 73%-50%, which is still a lot, but instead of creating equity with those other children, they just wrote about and published books about animals, which are perceived to be neutral, race neutral, although we know that they're anthropomorphized and therefore they're racialized, and they're gendered, and they're just made to seem human in so many ways.

So, when I show the two graphics side by side to students, and I say, "Are things getting better?" They usually go, "Uh!" That's pretty much how I feel about it. I think we have to be very careful when we make sweeping statements about, "Well, so and so just won the Caldecott, so and so just won a Newbery." You think that because somebody's on the New York Times bestseller list, that that means everything has changed and it's better. We just have to be careful. It can be more of an illusion than a reality that we're making.

EmbraceRace: Well, we had a Black president, you know.

Zetta Elliott: Right, racism is over. What's my problem.

Graphic from Phillip Nel's book, Was the Cat in the Hat Black?

Was the Cat in the Hat Black? by Phillip Nel, March 2019

EmbraceRace: So then, from the book by Phillip Nels, Was the Cat in The Hat Black? You also sent this graph I hadn't seen before. But wow! This is what it feels like going to a bookstore, right?

Zetta Elliott: It really does, right?

EmbraceRace: Yeah. You're looking for books for your Black kids, or for kids who, all kids who should be reading about Black kids. It's crazy.

Zetta Elliott: Yeah, you see that almost all of the books are realistic, or historical fiction, or non-Fiction. When you ask kids what books they most want to read, they'll tell you books about magic, fantasy, Sci-Fi, robots, spaceships. They know exactly what they want, and it's really frustrating that so many people, including kid lit scholars will look at these numbers and say, "Well, African American are understandably obsessed with the past and with slavery." It's like, no we're not. Actually, the person who's obsessed with that is the gatekeeper who keeps rubber stamping and green lighting these books about Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman, and Martin Luther King Jr. They're very important, we could have a moratorium, and it would be okay because we have so many of these narratives.

Graphic from Phillip Nel's book Was the Cat in the Hat Black?

Zetta Elliott: What we see getting published is then reflected in what we see gets awards. So, because there's only one award that is exclusively for Black authors and illustrators, The Coretta Scott King (CSK) Book Awards, if that award always goes to historical and realistic, and nonfiction books as we see in this chart, then what incentive would a publisher ever have to publish in any other category? So, we see it that CSK has never gone to a fantasy or Sci-Fi title. We've had Children of Blood and Bone, and Nnedia Okorafor has won every award in the world for her science fiction and fantasy. She has never won The Coretta Scott King Award. I just think there's something wrong with that. It's impacting what is available to our children. So, it's not the fault of the award committee, but I wish people would understand the correlation, that if you only give awards to certain kinds of books, publishers will only publish certain kinds of books. There's no incentive for them to take a risk on anything else.

Marti Dumas: I think that there is the misunderstanding that the only part of American culture that is exclusively Black is things that are connected to slavery, the slave trade, and the civil rights movement. Those stories are obviously very, very important. We don't want to make the mistake of forgetting history. So then, I understand why awards committees feel that they really need to make sure that they are highlighting those stories, so that we don't forget that.

"I realized really quickly that by third grade, that if I held up a book that had a brown person on the cover, that the children were going to guess, more than half of them, that the story was about slavery. Here's the problem, it usually was," says Marti Dumas.

Marti Dumas: However, when we come back to the idea of being able to imagine a future, it's really difficult. As a classroom teacher, one of the things that you do is, when you are going to do a read aloud, you take your little book, and you hold up the cover, and you ask the children what they think the story is going to be about. I realized really quickly that by third grade, that if I held up a book that had a brown person on the cover, that the children were going to guess, more than half of them, that the story was about slavery. Here's the problem, it usually was. So then, I think that those stories are very important, but also, I think that having a balance of other stories is just as important at this point. Maybe not always, but certainly at this point.

EmbraceRace: Then, there's the vicious cycle of what's published, and what's available to get an award. Also, when you think of kids just having that reaction, which affects what they want to read and if they want to read at all, right?

Zetta Elliott: Yeah.

Marti Dumas: So that, if you see a book that has a brown person on the cover, and you think it's going to be about slavery, then you think, "I don't like books with brown people on the cover." So then, you don't pick those up in the bookstore, you don't ask for those. That's self-perpetuating.

Zetta Elliott: Then, you also have the situation where I've had so many teachers say to me, "I wish there were more books that had kids of color in them that weren't about race." Because the implication is that, if there is an issue like civil rights, or oppression or injustice or something, then that book is about race and therefore, it's not enjoyable. Therefore, it's not fun. Therefore, it's oppressive to the child, as though Harry Porter is somehow not about race. Yes it is.

I mean, I'm someone who writes about the past. I do write about slavery quite a bit, and it is frustrating to have to say to a child, to have this pitch, like when I'm talking about the African burial ground, how do I have to make that interesting. I do think that, that's a moment where speculative fiction is really useful. If I say I want to make the past present, I want to make the past relevant, I want to make the past mesmerizing, I want to make it fascinating and compelling and exciting. Then, I can introduce ghosts. Kids love ghost stories. Then, I can introduce time travel, or I can play with alternate history and start tweaking history a little bit so that they're like, "Did that happen? Did that really happen?" Then, they have to go look it up to find out.

So, I think fantasy in a way is that door, it's that portal into the past that allows kids not to feel shamed and humiliated, because a lot of times, that's what they think when they think of slavery. They think it's Black people being debased, and why would I want to... I want to watch Black Panther. Well guess what? We could talk about Black Panther and still be talking about the past and the future. So, that whole Afro-futuristic, what Marti was saying before about the concept of time, and being able to offer kids a way in and out, in and out of time, and to reshape time even, I think that's a really powerful tool to give young people.

EmbraceRace (Andrew): Earlier on, Marti, I just want to pick up on a thing you said. If you can’t see an alternative from the present, then it may be hard to see the present. That imagining alternatives [or reading about imagined alternatives] makes it easier to reflect on what is actually happening. What I'm wondering, I've done a little bit of work where it became clear to me that, we generally, and in my case it was social justice folks, professionals who are dedicated to the work of making the world better, whatever that might be, had a very hard time, imagining what is a substantially better world would look like.

I’d ask, if you succeed in your work, 20 years have passed, not 200 years, 20, 25 years, what does that look like? That was very hard for people to answer. So, I'm wondering, when you are maybe articulating that vision, whether it's fantasy or it's science fiction, where do you draw your inspiration from? How do you think about... What would much different and perhaps much better look like? How do you start to piece that together?

Marti Dumas: I think that I start with exactly that thought, which is, how is the thing now, and the way that I see it? Because obviously, my view is limited, we're all limited in the number of angles that we have, in our vision. But, where is it that that piece starts now, and then how might it be different if X barrier were not in place?

For example, I love dragons. Just love, love, love dragons, and was always toying with the idea of writing a dragon story. But, I knew that the dragon story that I wrote would be in our world, and would not leave our world. So, there would be no alternate plane, nothing like that.

So, I was trying to think, who would be able to have a dragon, incubate and care for a dragon, and literally have no one notice. I was like, it's probably a person who is often overlooked. The person that I actually thought of was my mother. My mother was a dark skinned, tiny, beautiful but not to the European standard beautiful, person. Her brothers, she mostly had brothers, but her brothers and sister made fun of her because she was the darkest one, and dip, dip dip. All those kinds of things. She is to this day, the smartest person that I've ever met in my entire life. That's not said through the lens of just a child looking up to their mother. She was legitimately, ridiculously smart, and incredibly overlooked.

So then, I was like, what would have happened if a person like my mother hadn't had the barriers that she had? How could that have flourished? The story starts from there. Then the story just writes itself after that. You're just like, "Oh, okay," and you roll forward. But that, I think that kind of, exactly what you just said, that kind of like, "Okay, what do we have now, but what could be possible?" Then, that just makes an infinite number of angles. So, if you wrote that same story, your story would end up being completely different because, your angles of possible would be a little bit different than mine.

EmbraceRace: That would make it possible.

We should probably get to the readings.

Marti, maybe you want to start because you were just talking about, even though we're all reading about dragons tonight, do you want to start with your reading, and just intro it a little bit?

Marti Dumas: Sure, we can. I will read to you guys from Jupiter Storm, which is the first book in the Seeds of Magic Series. It is not a book birthday for us, but I think we still have three weeks left before the second book in the series comes out. I'll just read you the first chapter. It shouldn't need very much introduction.

To watch Marti read from the first chapter of The Dragon Keep (December 2019), click on the video button and move ahead to 40:20.

Marti Dumas reads: "Jacquelyn Marie Johnson was exactly the kind of girl she should be, tiny, talkative and sharp as a tack. She liked paper dolls and long division, and imagining things she'd never seen. But most of all, Jackie liked being in charge, and that was a good thing, because she was also really good at it. The students in Jackie's school were the most well educated assortment of toys on the planet. They knew all of Aesop's Fables, and the Tales of Compere Lapin in English and French. Their multiplication backs through nine, the difference between area and parameter, and in theory how to make shrimp and mudfish stew. None of the toys were allowed to use the stove of course, but they could recite the recipe and preparation techniques by heart.

"Without Jackie's guidance, the toys would have been a truly unruly lot. This was also the case for her brothers. There were five of them, Jacob, John, Jonah, Judah and Sam. Jackie wasn't the oldest, and she wasn't the biggest, but she was the most in-charge. Jackie's mother knew she needed to be in-charge of things, important things. So, she gave Jackie important responsibilities. For example, Jackie was in-charge of watering the plants, Jackie was in-charge of adding things to the grocery list, and every afternoon, Jackie was in charge of getting all five of her brothers to come inside for dinner. This was the hardest job of all, but it wasn't hard for Jackie. Even though her brothers were all over the neighborhood, doing all kinds of things, all she needed to get them inside was a metal pot, a wooden spoon, and a stern look.

"She would clang the pot three times, call each boy by name, then clang the pot once more for emphasis. The boys would come running when they heard her signal, but just in case any of them had a mind to be sassy with her about how the street lights were not on yet, and it was too early to come in, after she had finished banging on it, Jackie would put the pot on the porch, bottom side up and step up on it like it was a stage or a throne. Her perfectly polished Mary Jane's glinting in the early evening light. Standing on the pot, Jackie was tall enough to use her stern look to stare away all the excuses and the reasons why, so that all five brothers washed their hands at the hose outside, and filed into the house as quiet and orderly as a communion line. The neighbors marveled at her. Some of them laughed, but it was only the laugh people do sometimes when they're pleasantly surprised. Who could blame them. It was impressive to see someone so little commanding such authority, even when you've seen it many, many times before.

"On this particular day, after the neighbors had gathered to watch Jackie and her brothers inside, they were too busy smiling with each other, and chuckling knowingly about Jackie's little ribbons and her shiny little shoes, to notice when Jackie noticed the egg."

EmbraceRace: That's awesome. Nice read.

Zetta, what do you say?

Zetta Elliott: So, I think to go back to your question about how to write, it seemed like you were asking, do we have a utopian vision. I don't think of myself as much of a futurist. I don't think a lot about what the future's going to look like. I think I'm more backward looking, I tend to be more invested in the past. But, when I met Angela David, she said something that has stayed with me, and I'm still not sure I completely understand it. She said, her parents prepared her to live in a world that didn't yet exist. I do sometimes wonder if as authors we should be doing that, and we should be pointing to... I always say, "Art doesn't just show it's real, it shows what's possible."

I'm such a realist, and I'm so invested in telling kids the truth, and not sugar coating it, that I think sometimes I don't think about whether or not I'm offering them a sense of how another world might look or be, or what's possible. I'm reading Pet right now, by Akwaeke Emezi, which is amazing. She's doing this radical utopianism in a way that just it's mind blowing. I can't do anything like that.

In The Dragons in a Bag series, I wanted to show a kid who was living in a Brooklyn that was recognizable. That to me meant not just talking about landmarks, but talking about gentrification.

As someone who did leave Brooklyn a year ago, a little over a year ago because the prices were so high, Brooklyn is my heart, and it still is, I love it, but it was changing. I wanted to talk about what ends up getting lost when communities gentrify. But, how do you make that relevant to eight year old kids?

Well, you talk about the fact that Brooklyn used to be hospitable to certain creatures, and to magic, and now suddenly, the magic is drained out of Brooklyn. Those creatures no longer have a place to be. So, do they belong in the place where they're born, not that I'm talking about birthright citizenship, but do they belong in the place that they're born, in the realm of magic? Is there a way for them to become migrants and to be embraced and assimilated into Brooklyn? Or, do they have to have accommodations? What are we going to do with these dragons?

In the first book, Jax is an apprentice to a witch, who's trying to deliver three baby dragons. He ends up getting two to live around with magic, but the dragon thief prevents him from getting that third dragon there. So, the chapter that I'm going to read is chapter two. I'm just going to read a couple of pages. In the first book, Ma, his cantankerous witch is a key figure for Jax. In this sequel, he has a problem because Ma can't help him right now.

To watch Zetta read from the second chapter of The Dragon Thief, click on the video button and move ahead to 45:25.

Zetta Elliott reads: "Ma won't wake up, and it's all my fault. I had one job, one job and I blew it. I'm probably the worst witch's apprentice ever. But, Ma gave me a second chance. We left the realm of magic, and came back to Brooklyn to find what I left behind, a baby dragon. But, since we've been back, Ma just hasn't been her usual self. I mean, I've only known her for about a week. At first, I thought she was my grandmother, but she's not. Ma's a witch. She can be cranky, but deep down, Ma's not so bad. In fact, she's pretty cool for an old lady. I was looking forward to learning more about witchy stuff, but that can't happen if Ma won't wake up.

"My grandfather knows about magic too, but he's not here right now. Ma and I left him in the other realm with sis and Elroy. Mom agreed we can move in with Ma until our landlord fixes our apartment, but he's the worst landlord ever. So, mom is over there a lot of the time making sure he does everything the judge ordered him to do. That leaves me alone with Ma and her stranger apartment. At first, she just napped a lot. I'd sit in the chair beside her bed, and try to make sense of the strange words she muttered in her sleep. But, her naps got longer, and longer, until finally Ma just stopped getting out of bed. Now she doesn't eat or go to the bathroom, she only woke up once when she heard us talking about what to do. Momma's friend Afua came over to check on Ma, she's a visiting nurse. After examining Ma, Afua said her vital signs were good. "It could just be extreme fatigue," Afua said. "Has she been under a lot of stress lately?" Momma looked at me, and I looked at the floor.

"Ma was looking forward to retirement, but she had one last job to complete. I said I'd help her, but then everything went wrong. Now, it's up to me to make things right. I asked Afua what we should do if Ma didn't wake up. "Well, I guess you'll need to call an ambulance and take her to the hospital," Afua said. All of a sudden, Ma sat up and barked, "No doctors," before collapsing against her pillows. A few seconds later, she was snoring soundly. That's how Ma has been for the past couple of days.

"I'm on spring break, so I can stay with Ma while momma's at work. There's not much to do in this apartment. Ma doesn't own a TV, so I spend my days flipping through the many books in Ma's living room. There's a whole wall covered in bookshelves, but so far, I haven't found anything about how to break a sleeping spell. I never used to believe those fairy tales, but right now, a spell is the only thing I can think of. Why else won't Ma wake up? I kissed Ma's cheek just to see if that might work, but I'm no prince charming, and Ma's no sleeping beauty."

EmbraceRace (Andrew): Lovely. Lovely.

EmbraceRace (Melissa):Nice. Yeah, looking forward to reading the rest. Thank you. That was beautiful. I just wish we had those books when we were younger, right?

EmbraceRace (Andrew): Indeed. We have a little bit of time left, lots of questions, a couple of which were woven into the conversation already. One of very specific question, somebody wants to know the title of the essay about decolonizing children's literature, and if it's available.

We have a couple of questions actually, and you mentioned this Zetta, about Afro-futurism, do you want to say a word about what that is?

Zetta Elliott: Oh dear.

EmbraceRace: And the extent to which fantasy YA authors are part of this movement.

Zetta Elliott: Okay. I'm going to need Marti to back me up on this, and fill in all the blanks. Because like I said, I'm not much of a futurist, so I'm not that invested in thinking about Black people in outer space or in some future state. But, I will say that Nalo Hopkinson (@Nalo_Hopkinson) has said some of the smartest things I've heard about Afro-futurism.

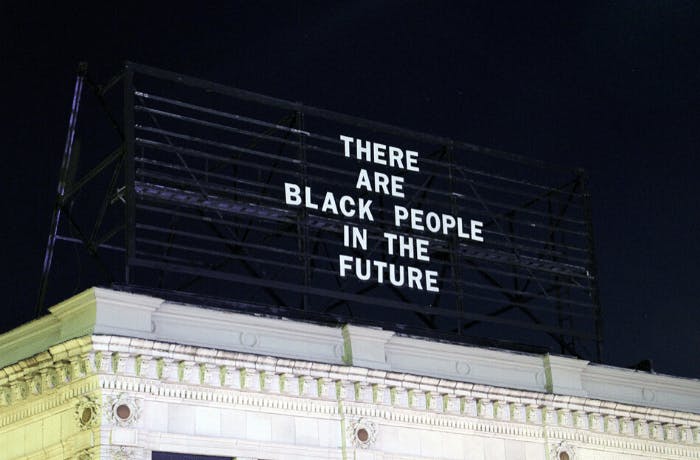

Zetta Elliott: There is an artist … Alisha Wormsley, who has this massive billboard that says, "There Are Black People In The Future." It's really quite radical to actually imagine Black people, and project them as having a future when you're coming from a history that has largely, in this country certainly, been about extermination and oppression.

So, if people have basically tried to destroy you, and have tried to make you destroy each other, and have pounded at your self-esteem and your sense of identity and self-worth, then for you to imagine that you have a future is actually quite radical. So, Afro-futurism for me is a way that Black people think about themselves in relationship to time.

It doesn't mean they're not thinking about the past, and I would certainly argue that the same code or principal of looking to the past for the thing of value to bring forward, that's certainly, I think, Afro-futuristic. But, there's also recognition that for Black people in the United States especially, time can be cyclical. So, if you don't know your history, you really might find yourself in that loop going around and around.

I think of Colson Whitehead's zombie novel Zone One, where he imagines the second Reconstruction. So, if you don't know how the first Reconstruction ended, watch out because we can end up in that loop again, and in that situation again, and all the gains you'd thought you made are stripped away from you.

So, I think of myself engaging with Afro-futurism in that, I am going into the past for the thing of value that will be a tool to help us shape a different future, and a different present primarily. But, if you're reshaping the present, then you're already thinking about the future. As Black artists, we have hope because, we wouldn't create if we didn't have hope. If you aren't imagining our community and our culture not just surviving but thriving, then really, what are you doing?

Marti Dumas: I am not going to add anything into what you've just said because it was amazing, except to also add on like an outskirt thing. which is that, I've read a number of things, and talked with a number of people who do make (people will yell, there will be disagreements, it's all good if they will all be in love hopefully) a distinction between African futurism, and Afro-futurism.

Zetta Elliott: You went there.

Marti Dumas: Okay. There are, as Zetta pointed out earlier, many people of African descent in the Americas are not aware of their specific African origin because of the transatlantic slave trade. So then, that distinction sometimes can be important because, for some of us, it is as much a hopeful reconnection as much as it is a delving into the past. It may not be our specific pasts. I know for me personally, I wrestle with the idea of pulling in cultural pieces from cultures that are not my own.

Everyone should wrestle with this, whether or not you end up doing it is a completely different question. But, really wrestling with the idea of pulling in cultural pieces that are not from my own specific culture because in a way, I really feel like I'm wearing a mask. It wasn't mine, and I'm taking and borrowing, and almost colonizing with my Americanness someone else's culture. So then, that can be a little bit touchy, yet, it's a thing that we need to think about as we're moving forward, like how is it that we would be able to embrace that without actually knowing the specifics of our past, like embracing nebulousness, I don't know, it could get weird.

Zetta Elliott: Wakanda.

Marti Dumas: Indeed, indeed.

EmbraceRace: That went by really quickly. I want to apologize to folks that Andrew and I totally went off with these guys because we were just so into it. There are a lot of questions about recommendations as well for littles and for bigs.

Happily, Zetta and Marti gave us suggestions, book sites as well as Marti and her son came up with a fantastic list of books they're really excited about. Check those out in the resources below.

Thank you so much you guys. This was really wonderful.

Everyone go out, buy their books, and look at their recommendations. Really, all kids need these books that we're talking about. So thank you.

Marti Dumas: Well, thank you.

Zetta Elliott: Thank you.

And if anybody has a question that we didn't have time to answer, I'm not a huge Twitter person, but if you tag me, @Zettaelliot, I will come over and answer your question. Thanks so much to the both of you, Melissa and Andrew for giving us a chance to be in dialog. I don't get to see Marti all that often.

Marti Dumas: Yeah.

Zetta Elliott: So, this has been really nice.

Related Book Resources

Marti Dumas and Her Son Share Favorite Middle Grade Fantasy Fiction that Features Children of Color

"The following is a list of modern titles that both my son and I have enjoyed. It is not an exhaustive list, but it is a good place to start if you like fantasy adventures and want to make sure that the main characters in those stories reflect the diversity of the world we live in." Thanks, Marti!

Reading Black Futures

Professor Stephanie Toliver's site is dedicated to promoting science fiction, fantasy and horror by Black authors.

Charlotte's Library

For reviews of multicultural speculative fiction from picture books through YA and including graphic novels, check out this list on the Charlotte's Library blog.

Zetta Elliott's blog

Zetta keeps a list of Black-authored speculative fiction, both for middle grade and young adults, on her blog.

Marti Dumas

Zetta Elliott