Reading Mike Jung's "Unidentified Suburban Object" with my Kids, Part II

By Megan Dowd Lambert

The author’s four adopted children. Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

As I noted in my previous Embrace Race post about Mike Jung’s middle grade science fiction novel, Unidentified Suburban Object, I hope many child readers will discover its major plot twist on their own. But even if they find out that protagonist Chloe Cho is an extraterrestrial alien (and not Korean American as her parents raised her to believe) before reading the book for themselves, there’s much more to be savored and appreciated about Jung’s book beyond its stunning reveal. During our shared reading, my ten- and eleven-year-old kids, Caroline and Stevie, and I ended up talking about children’s rights to their own stories and histories and the work we need to do as a society to promote and protect those rights. These conversations were informed by my children’s experiences as transracial adoptees.

In our family we talk openly about their respective life histories. Although I write generally about adoption and about my experiences as a White mom with kids of color, I do not write or speak publicly about my children’s birth families or their particular adoption stories because these are not my stories to tell. This conviction is related to the inverse notion that my kids are entitled to know anything and everything they want to know about their birth families and the circumstances that led to their placements in foster care and their eventual adoptions into our family, some as babies, and some as older children.

In Jung’s novel, Chloe is not an adoptee, but her parents have cut her off from her history and her heritage through their lies and secrecy, which resonates with some of the sad history and problematic discourses around adoption, transracial or not. Here, I don’t just refer to circumstances in which adoptees’ parents hide their adoptive status (which I believe, or at least hope, is a rarer occurrence than it once was), but also to laws that keep adoption records sealed, and to manipulation or outright lies that result in adoption against birth parents’ wishes.

Despite their dishonesty, Jung’s novel doesn’t paint Chloe’s parents as unsympathetic characters, and it’s clear that their motivations for hiding the truth from their daughter are good. They want to protect her. They are personally traumatized by the losses they’ve endured. They are afraid. My children recognized all of this as we read together, but they aligned themselves with Chloe and kept coming back to the injustice of it all:

“They lied to her,” said Stevie. “They lied and lied and lied.”

“And now she’s supposed to lie too,” said Caroline.

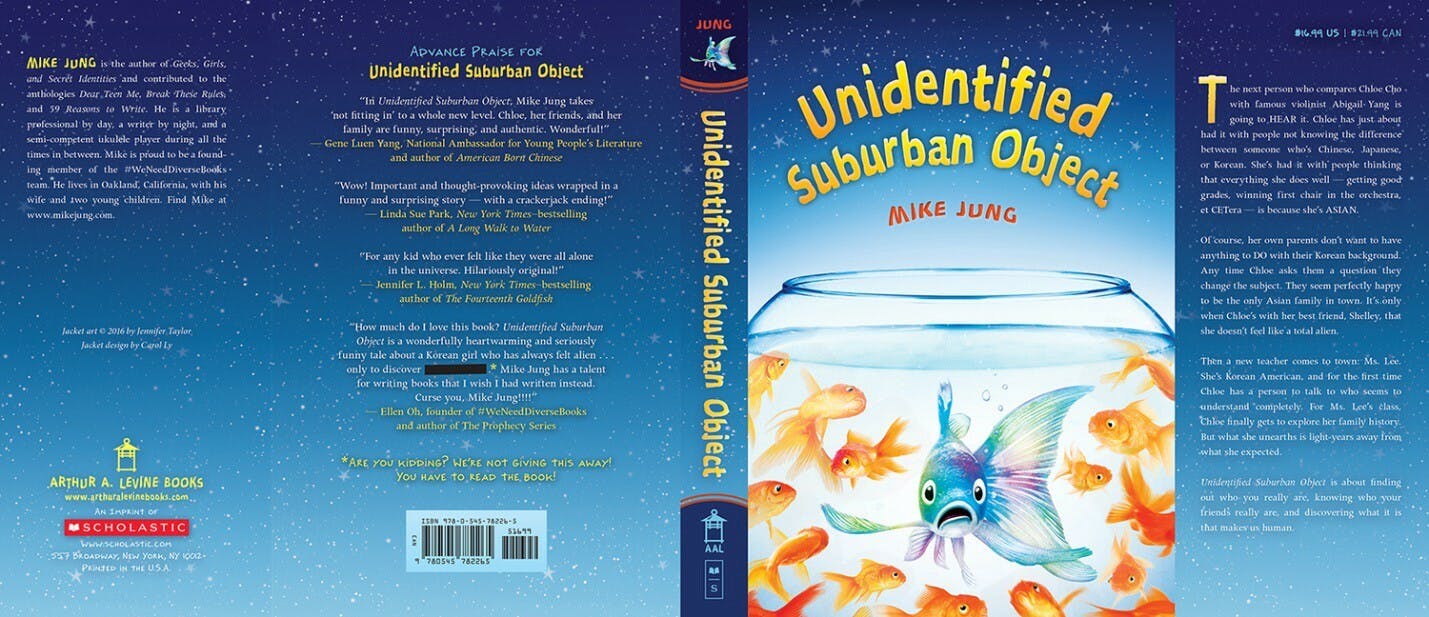

Full jacket from Mike Jung’s novel Unidentified Suburban Object Arthur A. Levine Books, Scholastic 2016 Source: http://www.carollydesign.com/unidentifiedsuburbanobject/

Within these lies are losses for Chloe: loss of trust in her parents; loss of ties to what she’d falsely believed to be her heritage; and loss of stability in her identity. I know that adoption itself is premised on losses sustained by birth families and adoptees — losses that are compounded by transracial adoption when it severs connections between children of color and their respective cultures of origin. And furthermore, I know that as a White person I cannot provide my children with a model of lived experience about what it means to be Black or Latina or biracial in our society, though, I can and do provide them with diverse books and other media, affirming cultural experiences, abundant love for them as their particular selves, and day-to-day conversations and interactions that support their developing, unique identities.

Although Chloe isn’t racially different from her parents, she experiences the sort of isolation from her heritage that I strive to keep my transracially adopted kids from experiencing. She thinks her mother and father won’t answer her questions about Korea and their lives before they immigrated to the United States, but the truth is, they can’t. Explaining their decision to escape to Korea when they escape their doomed planet, Chloe’s father says on page 146, “‘Initially we decided to go to Korea because of all our physical similarities — it seemed like the best place to blend in. That turned out to be a mistake.’” Her mother continues, “‘It was the hardest place to blend in, because we so obviously weren’t Korean…We did it all wrong, everything from speaking the language to finishing a bowl of noodles. It was very, very uncomfortable.’” They end up settling in a nearly-all-white town in the U.S., where they can blend in as Korean-Americans because no one knows anything about Korea. The tragedy for Chloe is that because she is raised to think she is Korean she wants to claim this heritage, but she has no one to help her do so.

When she finds out that a new teacher at her school is named Su-Hyung Lee, Chloe is hopeful: “Was she Korean? Maybe I could talk to her about the stuff my parents always blew off. Maybe things actually would be different.” Even though I don’t “blow off” my kids’ heritage, and despite my efforts to support and nurture my kids’ since of racial identity and pride, I know I don’t get everything right. Reaching out to adult adoptees, and listening to or reading about their experiences is crucial — and I highly recommend Angela Tucker’s work at The Adopted Life and Mariama Lockington’s powerful recent piece “What a Black Woman Wishes Her Adoptive Parents Knew” that underscores the misguided, damaging impact of a “colorblind” approach to transracial adoptive parenting.

The author’s son with his Big Brother Mentor from the Adoption Mentoring Partnership. Photo credit: Andrew Drinkwater

Reading Lockington’s story and hearing and encountering many other similar ones over the years contributes to my knowledge that no matter how much I “do the work” myself, my children need other significant people, and particularly adult adoptees and people of color, in their lives. And so, we live in a diverse neighborhood, they attend public schools with diverse populations at which they’ve had teachers of color, and our community of friends includes people of color. One daughter has participated in a group for adopted teen girls that’s run by Adoption Journeys, and one of the best resources we’ve found is the Adoption Mentoring Partnership based at UMASS-Amherst, through which three of my kids have gained college-aged mentors who are also adoptees and who just spend regular time with them and act as caring adults in their lives. Most importantly, they have each other, and all of these experiences and relationships are providing them with pathways to their future selves, secure in their rightful place in our family and proud of their roots.

The author’s son with his Big Brother Mentor from the Adoption Mentoring Partnership. Photo credit: Andrew Drinkwater

My children also know that should they decide one day to try to develop relationships with their birth families, we will support them. Stevie and Caroline and I talked about this as we finished Jung’s book, which has an open ending that invites speculation about Chloe’s future possibilities for learning more about her family’s history, and perhaps connecting with others from the planet that her parents escaped. That conversation feels private, so I won’t share its details here, but I can offer the empathetic responses that they had for Chloe:

“That would be so happy for her!” said Caroline.

“Is there a sequel so we can see if that really happens? If she learns more about her family and where they come from?” asked Stevie.“Not yet,” I told him, but I hope there will be (calling Mike Jung?). In the meantime, I’m grateful that this science fiction novel offered me and my kids so much enjoyment and opportunity for talking about their lives in the real world.

Megan Dowd Lambert